It took me years to get this document. As much as I knew already, I was still stunned.

It took a legal battle before the Israeli Supreme Court for me to be allowed to see it. What it proves decisively is that before the same court, 44 years ago, a senior government lawyer presented an argument for the state that—let me put this delicately—has no connection to the facts, and the court accepted it. Army and government papers show that the same happened in two other key Supreme Court rulings early in the occupation.

I am retelling this now not just to set the historical record straight in light of new evidence, though that’s important enough. The affair also says a great deal about the role that Israel’s highest court has played, then and ever since, in giving a veneer of legitimacy to what the government does in occupied territory.

Original text of the inquiry report and further information

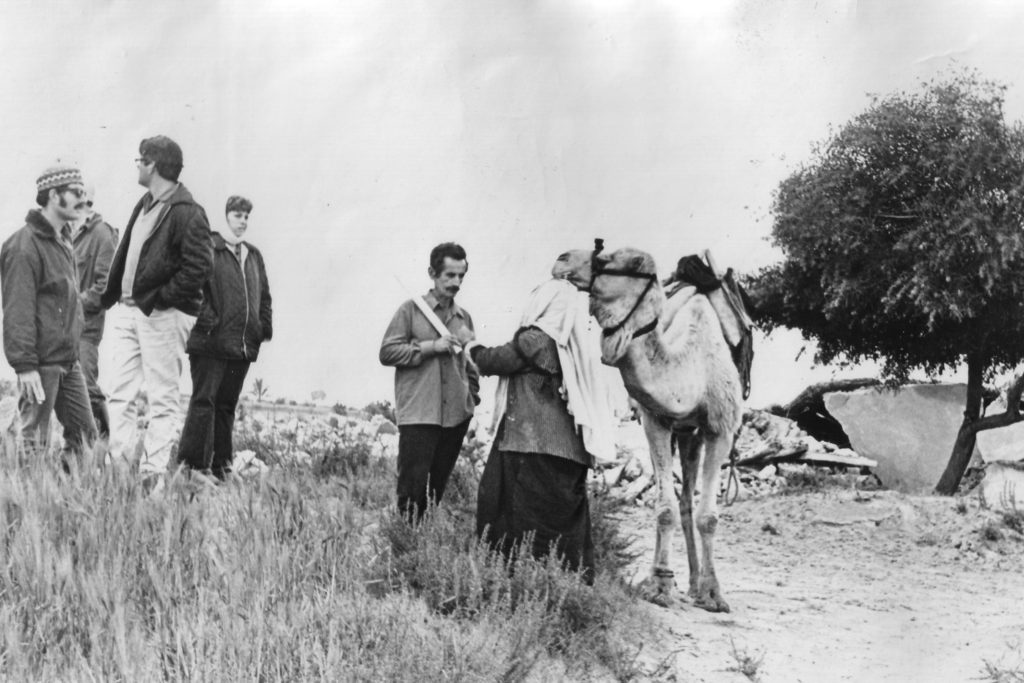

The expulsion began in the early morning on January 14, 1972, when Israel Defense Forces troops arrived at a Beduin community in the northeastern corner of the Gaza Strip, an area that Israel called the Rafiah Plain, and announced that everyone had to leave the area. That day they knocked over tents; the next day they returned and demolished houses. Over the next few weeks, nine Beduin tribes, somewhere between 5,000 and 20,000 people, were expelled from an area of at least 18 square miles.

When the International Committee of the Red Cross asked for an explanation from the brigadier general in charge of administering the occupied territories, it turned out that neither he nor the military chief of staff, David Elazar, knew about the expulsion. Lt. Gen. Elazar ordered an internal army inquiry. An anemic statement issued by the cabinet in late March said the inquiry committee found that “several commanders” had exceeded their authority. No names were given, but it eventually leaked that the most senior of them was Maj. Gen. Ariel Sharon, head of the IDF’s Southern Command. …