Haim Watzman

After Proverbs 9

Back then I told you everything, but you’re not up to date. You’re back from two years screwing the women of three continents and several islands, and there were things I wasn’t going to write on Whatsapp, no matter how secure it claims to be. Listen to me. That old Russian lady I hugged and kissed when she came over here to the bar at the First Station to say hello? I’ve learned more from her than from you or my professors at the university or any teacher I had in high school. Like I said, I sometimes spend Shabbat at her place instead of going home

“Your friends will think you’re a faggot,” is what you think the girl at the airport said to me. So lay it on, Gadi. I’m prepared. I’m prepared. What girl? The one who came on to me at the same time as that Russian lady.

I’d just gotten off the plane after my own mini-trek, two weeks in England the summer after we were discharged, that’s all I allowed myself because I wanted to get started at the university. You were already on your way to Patagonia or wherever, going south from Rio girl by girl. They were pretty spectacular, those photos you sent, and I don’t mean the mountains and the beaches. I’m sure I only saw half of them. But, hey, you have to admit it, when we were out together, it was me who the girls looked at. I’m a head taller, leaner, have a better smile. Yeah, you’re the one who took them home, when they gave up on me, but I got the eyes first, give me that.

“Is this the flight from London?” I hear two voices say simultaneously, one in each ear, just after I stationed myself at the luggage rack. I look to my right and it’s this really nice-looking girl, lithe and slender, like a swimmer or gymnast, dark hair but with the bluest eyes I ever saw in my life. I look to my left and it’s that lady.

“Yes,” I say to her, who tells me in Russian-accented Hebrew that her name is Sofia Klieger.

“Hey,” says the voice in my right ear. I turn and she’s got this really nice smile. I remember seeing her at the gate when we boarded. She says: “I hate this. Everyone’s so pushy.” She says that her name is Anat.

“My luggage is always last,” Sofia informs me. “It’s the story of my life. But I’m used to it. I wait.”

“Oh, there’s mine!” Anat points. She’s clearly apprehensive about forcing a path between the two Haredim blocking her way. I realize that she’s expecting me to get it for her, so I part the Hasidim and grab it.

“Thanks so much,” she says. And she gives me a hug, like I’m her long-lost brother.

“You travel England?” Sofia asks me. “Hike?”

“I planned to, but I ended up spending most of my time in the British Museum and the National Gallery.” I feel blood rushing to my head, you know why? Because at that very moment I’m thinking, Gadi’s going to say, what a hnun.

Anat’s got her bag but makes no sign of heading for the green line to go through customs. Instead, she peers around me at Sofia.

“I’m a lighting designer.” she says. “I was working on a show in London. Also, going to parties.”

“I went,” Sofia tells me, “to visit the grave of Ludwig Wittgenstein at the Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge.”

“Wittgenstein?” I say.

“The philosopher,” she explains. “You know, the one who said ‘Nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself.’ You never heard of him?”

“No,” I admit. “But he already sounds interesting.” Hey, Gadi, ever tried whispering that in the ear of a hesitant female?

Anat frowns as she looks me over. “I don’t think you were at any of them. I would have noticed.”

“He was for a time one of the wealthiest men in Europe,” Sofia continues. “But he gave away his wealth. He was from a family of Jews who had converted to Christianity; Brahms was a regular visitor at their house. Three of his four brothers committed suicide. He went to high school with Hitler, which maybe says something about what schools can do.”

“Hey,” says Anat, “You’re kind of nice.” Which was not true at that moment because I was ignoring her and listening to Sofia.

“Wittgenstein saved me when I kicked my husband out of the house ten years ago.” Sofia eyes the conveyor belt with a look of forgiveness, “I brought the bum with me from Kiev instead of leaving him there like I should have.”

“Wittgenstein saved you?” I’m like, really intrigued. But the girl keeps bothering me.

“Where are you going from here?” she asks.

I turn to her reluctantly and shrug. “I guess to my Dad. In Mevasseret. Nowhere else to go.”

Sofia continues her tale. “I spent a year shut up at home. Didn’t go out, except to work and back, didn’t talk to anyone. I ruined my life, I kept telling myself, and I deserve to suffer. My son was already on his own, living with his girlfriend, I’m stuck in Karmiel and he’s in Haifa and soon he’s got children and he calls twice a week but he works hard and he has to put his family first, I understand that.”

Anat puts a hand lightly on my shoulder “You don’t get along?”

I just stare at her. “You can come to Tel Aviv with me,” she offers.

“He’s in an insane asylum now, the alcohol ruined his brain. My ex-husband, I mean. Had I kicked him out in Russia, before we came to Israel, I would have an apartment today, they gave to single women but not to married ones. So I ruined my life.”

“I mean, why go home if that’s not where you want to be?” Anat says. “Maybe you need to try something different, after all that time in museums. Meet some fun people. Loosen up. Have a good time. Just suggesting.”

“And then I’m taking out the garbage one evening, when no one can see me, and next to the bin there’s this book. It’s in English. It says Philosophical Investigations, by Ludwig Wittgenstein. It’s a plain cover but somehow it catches my eye. I leaf through it. I My English isn’t bad, but I couldn’t make any sense of it. Then my eye fell on a passage that said this. It said ‘Is an indistinct photograph a picture of a person at all? Is it even always an advantage to replace an indistinct picture by a sharp one? Isn’t the indistinct one often exactly what we need?’”

“You don’t have a girlfriend,” Anat says to me. “I see it in your eyes.”

“It changed my life. I read through the whole book in two days and then I read it again. Wittgenstein says that …” She points matter-of-factly at the conveyor belt. “My suitcase.”

It’s huge. I’m barely able to grab it before the belt carries it away.

“What does Wittgenstein say?” I ask her.

“You can sleep on my couch,” Anat says. “Really, no problem.”

“My son is picking me up and driving me home to Karmiel,” Mrs. Krieger says. “I have a good dinner in the freezer, just waiting to be defrosted.”

Anat seems to realize she’s losing, but she doesn’t give up. She takes a business card out of her pack and slips it into the back pocket of my jeans. “In case you change your mind,” she says.

So, yes, I went home with Sofia. Stayed up all night talking philosophy with her, conked out on her couch, stayed another night. She’s a great cook. We’ve been very close ever since. Maybe once a month I go to Karmiel for the weekend.

Yes, Gadi, I have gonads, and all the equipment works very well. And I’m not a faggot, as you very well know.

And I have Anat’s card. I’ve been thinking about calling her. Why? Well, she seemed nice. And there’s a lot I want to tell her now. For me, it’s almost like they’re two parts of the same experience, like two ways of describing a scene. Or two ways of talking about love.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

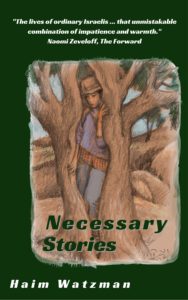

Necessary Stories, a collection of twenty-four of the best of Haim Watzman’s short fiction, is now available as an e-book, paperback, and hardback on Amazon and all other vendors. Click here for purchase links and more information.

Necessary Stories, a collection of twenty-four of the best of Haim Watzman’s short fiction, is now available as an e-book, paperback, and hardback on Amazon and all other vendors. Click here for purchase links and more information.

Haim will be speaking about his story Sin Offering at the Washington Square Minyan in Boston on Saturday morning, October 28, at American University in Washington DC on Monday evening, November 6, and at Upshur Street Books in Washington, DC on Tuesday evening, Nov. 7. See his speaking and performances page for more details. Too book future appearances and performances, contact him at hwatzman@gmail.com.

Receive email alerts of new Necessary Stories every month, and other pieces by Haim:

.love.