And middle age has its advantages. Going slowly, planning out each step, I take in more. The rains have ended, the squills are desiccated. I wonder whether the whorled stumps that dot our path are the bulbs of these autumn flowers, the remains of trampled or eaten plants. I ponder the Naftali highlands over the Hula Valley on the western horizon and point out the peak of Mt. Meron to my companion, who has gone this way dozens of times and never parsed the view.

Sixty years ago, I tell my son, the valley below was a huge swamp. Reeds and bulrushes grew in clumps an expanse just a couple meters deep, fed by the Jordan and its tributaries. Otters played and fat fish and frogs of breeds that lived nowhere else plied its gentle currents. And huge swarms of mosquitoes hovered over the shallows, in hunt of warm blood. One of the mosquito tribes was the dreaded anopheles, which injected virulent plasmodia into the bodies of the emaciated marsh Arabs, the only humans who dared live on the shores of the lake at the mire’s southern end. That is, until the Zionists came to the valley and built Yesod HaMa’ala and Rosh Pina, there to shiver and sweat with malaria.

At the bottom of the gorge we reach a jumble of huge boulders guarding a little Eden. A stream of pristine water burbles down from the ridge above and leaps, carefree over a ledge into a large pool below. An oleander with a fireworks fan of exuberantly pink flowers stands guard over the waterfall. A skink, stripes running down its back, emerges from a crevice to lap up a watery film where a drop from the torrent has landed.

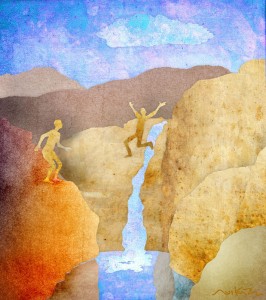

We strip down. My son steps up to a ledge that stands a good ten meters above the pool and jumps.

Now, I’m not the unadventurous type. Just two weeks before, on Independence Day, I arrived with some friends of mine at a similar spot as we trekked down the Euphrates. This is the river where the prophet Jeremiah went on God’s command: “Take the girdle you have upon your loins and arise, go to Perat, and hide it there in a hole in a rock.” But neither Jeremiah nor we were quite as adventurous as that sounds. We didn’t have to travel far. In Hebrew, the Euphrates is called the Perat, but the Perat, like Joyce’s Liffey, is not one but a multitude. It is one of the rivers of Eden, and it’s also the name of the wadi that begins at Anatot, the priestly village northeast of Jerusalem where Jeremiah grew up, and descends through the upended chalk strata of the Judean highlands down to the oasis at Jericho.

Batting our way on through towering bamboo-like canes that grow thick enough to make entire stretches of the riverside path seem like a Levantine avatar of the Mekong, we came to a spot where the stream tumbled over a pair of smooth, slide-like cascades into a deep pool. The path leads to a set of iron rungs that we used to climb down to a shady spot where we took a rest. Two of us undressed and jumped into the frigid water; three remained clothed and munched on the side. Coincidentally, but perhaps not, the two of us who jumped in were the two who don’t have married children. One of the shore sitters read out loud from a trail guide a recommendation: try sliding down the waterfall into the pool. Alone, I climbed up the iron rungs, waded into the stream, and slid. I have pictures to prove it.

It’s always a surprise to find naturally flowing water in this country. Maps and accounts from the beginning of the twentieth century show myriad pools, springs, and brooks where today one finds dry hollows and channels. Israel is not a country to let a water flow lie. This began long before there was a country. The officials and planners of its pre-state institutions engaged in long campaign against nature’s arbitrary dictates about where human beings could live and farm. They outwitted the lay of the land by diverting, pumping, and piping water from low places to high places, from this basin to that basin, from freshwater spring to brackish well, from moist north to dry south. Virgin fields were wed to the plow, settlements could be built the length and breadth of the land.

These were the projects of a youthful society, limber, flexible, overconfident, stimulated rather that deterred by the whiff of danger and the possibility of failure. The man most responsible for the redistribution of Israel’s water was Simcha Blass, an argumentative engineer who thought big. He was the tech guy behind the founding of Israel’s national water company, Mekorot; Levi Eshkol oversaw, Pinhas Sapir managed and raised the money; Blass drew up the actual plans. The idea that a single company should plan, exploit, and sell the entire country’s water supply was not an obvious one in the 1930s. It took a lot of wheedling, politicking, and daring. Fortitude, confidence, and not a little luck stood in their stead, and by the time independence came around, the new country came equipped with a national water network.

The state of Israel was not born as an infant—it came into the world already well into adolescence. Seeking to absorb huge numbers of immigrants and fortify its defenses, its leaders believed it absolutely essential to settle its nether and border regions, especially the Negev desert. Blass came to the rescue with another big idea, complete with sketches—building a huge pipe to bring the waters of the Jordan and Lake Kinneret from the Galilee to Israel’s southern wilderness.

At about the same time, the Jewish National Fund, its role as land procurer for the Zionist project superseded by the new Jewish polity, looked around for a new challenge. The Hula swamp looked like land gone to waste. This wasn’t, as some have painted it, a particularly Zionist form of hubris. All around the world national planners viewed swamps as places where nature had gone wrong. Numerous projects, from the British fens to the Everglades, sought to reclaim mosquito havens for human habitation and agriculture. Of course, here it was good for pr as well. Large sums were raised overseas with pleas about malaria-stricken pioneers battling the anopheles for control of their Galilean kingdom—no matter that DDT had eliminated the mosquitoes, and the danger of infection, some years before.

So immigrant laborers were brought in. Channels were dug, springs diverted, and in 1958 the sluices were opened and the Hula marsh’s waters drained into Lake Kinneret. The desert bloomed, but the swamp withered.

You can’t do great deeds if you spend too much time worrying about how things might go wrong. Young people think more impulsively and with less deliberation; that’s why we draft 18-year olds and make 20-year olds officers. It’s also why we don’t let those same kids run the country. To found and defend, you need people who are eager to dive off cliffs. If you want to keep the country going, you need more forethought, and hindsight.

The big water projects of Israel’s early years turned out not to be unmixed blessings. The national water system’s project of making water available everywhere spent lots of money piping an essential resource to remote places, at the same time as it encouraged overuse of the country’s springs and aquifers; as fresh water was pumped from the ground, sea water percolated inland to replace it. The national water carrier completely upset the balance of the Jordan valley system; virtually no water flowed from the Kinneret into the lower Jordan, whose flow is a ghost of its former self and which flows at all only thanks to the sewage dumped in it; and the Dead Sea, deprived of its main influx, is dying a slow death.

We don’t call swamps by that name any more. Now they are wetlands and we understand that they are valuable and seek to preserve them. Not only are they home to native animals and plants, but they filter and cleanse water. When the Hula swamp died, Lake Kinneret grew dirtier, upsetting its ecological balance. A lot of the farmland salvaged from the swamp turned out not to be so fertile, and the peat deposits under some of it were prone to spontaneous subterranean conflagrations. Most scientists and planners now view the draining of the swamp as a huge mistake.

My son leaps. He plummets the ten meters and makes a huge splash in the pool. I look over the edge and do what he did not: I think twice.

“You’re not going to jump?” he sputters from the icy water.

“Oh, I’m jumping,” I say. “You don’t think I’d come all the way down here and not jump, do you?”

And I do leap into the freezing water. But with more judgment, from a lower ledge.

Links to more Necessary Stories columns