Haim Watzman

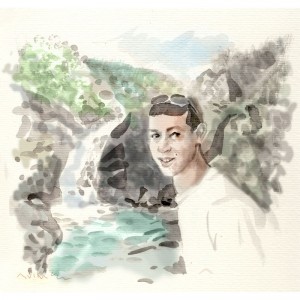

This is an English translation of my annual dvar Torah for Pesach in memory of my son Niot z”l, whom we lost twelve years ago during Pesach. A pdf file of the Hebrew original, which appears in this week’s issue of “Shabbat Shalom,” the weekly Torah sheet published by Oz Veshalom, the religious peace movement, can be downloaded here .

Act One: A prologue that brings the audience into the play and lays the ground for the way the acts that follow will be experienced.

Act Two: The story of the Exodus from Egypt or, more precisely, a set of stories that touch on the way the story of the Exodus is told—the Maggid.

Act Three: The sacred central ritual of eating the Pesach offering, the required festive meal, and the offering of thanks for the meal with Birkat Hamazon, the grace after the meal, and for the redemption with the psalms of the Hallel.

Act Four: The happy ending, a musical finale that raises the spirits and sends the audience out of the theater with a smile and a bounce in their step.

The first act is the most unexpected of the four parts. At first glance it looks technical and dry; it seems not to have much to do with what follows. But, in fact, the opposite is true. It is structured around two motifs that are the very essence of the subsequent acts. Without Act One, the two central acts, those of the story of the Exodus and of the eating of the offering, would be understood in an entirely different way.

Bad sex makes good books. Let me put that on the table, or in the bedroom, or even on a grave, as in one of the four Hebrew novels I have come to praise in this essay. In our times, when works of fiction are expected to delve into the most intimate parts of their protagonists’ souls, bedclothes, and anatomies, and to provide at least one erotic episode to give a lift to all three, the ability to write a convincing and moving scene in which the sex act is portrayed as indifferent, unfulfilling, boring, or frustrated by impotence is the mark of a great and original talent.

Bad sex makes good books. Let me put that on the table, or in the bedroom, or even on a grave, as in one of the four Hebrew novels I have come to praise in this essay. In our times, when works of fiction are expected to delve into the most intimate parts of their protagonists’ souls, bedclothes, and anatomies, and to provide at least one erotic episode to give a lift to all three, the ability to write a convincing and moving scene in which the sex act is portrayed as indifferent, unfulfilling, boring, or frustrated by impotence is the mark of a great and original talent. This is an English version of the Hebrew dvar Torah that appears in issue 1276 of

This is an English version of the Hebrew dvar Torah that appears in issue 1276 of  The lupines on the two sides of the barely discernable path are darker than the ones I remember from last year, perhaps because a small cloud his blocking the sun’s rays, or because rain and chill winds prevented us from getting here on recent Saturdays, causing us to miss the blooms at their height. Or perhaps the reason is that the approaching Pesach holiday brings us closer to the season of our inner darkness, the affliction of losing our son

The lupines on the two sides of the barely discernable path are darker than the ones I remember from last year, perhaps because a small cloud his blocking the sun’s rays, or because rain and chill winds prevented us from getting here on recent Saturdays, causing us to miss the blooms at their height. Or perhaps the reason is that the approaching Pesach holiday brings us closer to the season of our inner darkness, the affliction of losing our son  Nothing is more present than an absence. In an event, as in a story, that which is not stated explicitly, and the person who does not speak, are sometimes the most important. This truth stands out in our family on Pesach. This year we will gather for our Seder for the eleventh time without our son and brother Niot, who left us after the first day of Pesach and never returned.

Nothing is more present than an absence. In an event, as in a story, that which is not stated explicitly, and the person who does not speak, are sometimes the most important. This truth stands out in our family on Pesach. This year we will gather for our Seder for the eleventh time without our son and brother Niot, who left us after the first day of Pesach and never returned.

I’ll begin with a story. Actually, I’ll begin with the same story that Pinchas Leiser told on Rosh Hashanah. His story was about the way the great Hasid Rabbi Levi-Yitzhak of Berditchev chose a shofar blower one year. There were three candidates and Rabbi Levi-Yitzhak interrogated them about the kavanot—the intentions they had—when they blew the shofar. The first said that his intention was to confuse Satan. The second said that his intention was to rouse the higher spheres to have mercy on the Jewish people. The third said simply that he had ten hungry children at home. The rabbi from Berditchev chose the third one.

I’ll begin with a story. Actually, I’ll begin with the same story that Pinchas Leiser told on Rosh Hashanah. His story was about the way the great Hasid Rabbi Levi-Yitzhak of Berditchev chose a shofar blower one year. There were three candidates and Rabbi Levi-Yitzhak interrogated them about the kavanot—the intentions they had—when they blew the shofar. The first said that his intention was to confuse Satan. The second said that his intention was to rouse the higher spheres to have mercy on the Jewish people. The third said simply that he had ten hungry children at home. The rabbi from Berditchev chose the third one.

Many years ago, when I worked as a journalist, I attended a press conference at a conservative research institute in Jerusalem. I don’t recall exactly what the subject was, but I do remember that the institute’s director, who had served in an elite unit in the US Army, claimed that he could prove scientifically that the State of Israel had been in the right in a recent military action that had been loudly criticized by the rest of the world. After I and several other reporters settled ourselves in the small meeting room, he rose to speak. “I’ll start with the creation of the world,” he began. Realizing that the press conference would be very long and grueling. I mumbled an excuse of some sort, got up, and left.

Many years ago, when I worked as a journalist, I attended a press conference at a conservative research institute in Jerusalem. I don’t recall exactly what the subject was, but I do remember that the institute’s director, who had served in an elite unit in the US Army, claimed that he could prove scientifically that the State of Israel had been in the right in a recent military action that had been loudly criticized by the rest of the world. After I and several other reporters settled ourselves in the small meeting room, he rose to speak. “I’ll start with the creation of the world,” he began. Realizing that the press conference would be very long and grueling. I mumbled an excuse of some sort, got up, and left.

At the beginning of the Seder, before we begin the magid, the telling of the story of the exodus from Egypt, we perform a ritual called yahatz. We break, according to most customs, the middle of the three matzot that we have placed on the table along with the other signs of the holiday. We set the larger piece aside or conceal it so that it will serve after the meal as the afikoman.

At the beginning of the Seder, before we begin the magid, the telling of the story of the exodus from Egypt, we perform a ritual called yahatz. We break, according to most customs, the middle of the three matzot that we have placed on the table along with the other signs of the holiday. We set the larger piece aside or conceal it so that it will serve after the meal as the afikoman.