“Have a biscuit,” I offered, pushing a plate of petit beurres toward him. “Sorry I don’t have anything better.”

He giggled. I took a sip of syrupy Turkish coffee and a bite out of one of the flat and fluted cookies, cardboard with a whiff of artificial vanilla. I picked up my pen, and waited. He made no move toward the plate of biscuits nor toward his own small and steaming glass. I adjusted my olive-green parka and ran my hand over my shoulder to make sure that my first lieutenant’s stripes were clearly visible. Like the sun straining to heat Neptune, a double-coiled space heater glowed forlornly. A naked bulb overhead cast barely enough light for me to make out the lettering on the form in front of me. Not much more managed to make its way through the grime-streaked small window at my back.

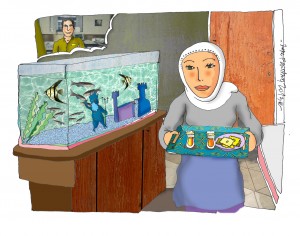

illustration by Pepe Fainberg

He rocked in the metal chair with the uneven legs that I’d grabbed from the deputy brigade commander’s office, his rifle on his lap, his arms at his sides, his back straight, one side of his shirt tucked firmly into his baggy fatigue pants and the other side nearly hanging out. Some fine and curly chest hair was visible through the two-button opening in his shirt. His eyes surveyed me and I felt resentment welling up inside. He thinks I’m fat, I thought. I am fat. I pushed the cookie away, waited for him to speak, and when he didn’t pulled it back toward me and took another bite. His face was delicate, soft, not at all like the chiseled and determined ones that most of the brigade’s enlisted men displayed. His expression was dreamy, happy, but it looked like a fool’s cheerfulness.

I picked up my pen and asked: “Do you know why you’re here?”

He giggled again and shrugged. “Udi sent me.”

“Do you know who I am?”

“You’re Aliza,” he said.

I waited.

“The brigade personnel officer.”

“Good,” I said. I picked up a printout of Udi’s e-mail. “Your company commander says that he thinks you might not be right for the Givati Brigade.”

He stiffened. “Not true,” he said. “I’m a good soldier. I carry whatever they give me to carry for as long as I have to. I lie in ambushes and help my friends. What does he want?”

“He says here,” I pointed, “that you disappear.”

He giggled again. “But I’m right here,” he said. “I’m always right here.”

“‘On desert maneuvers one afternoon last month,’” I read, “‘the soldier Ami’s squad was sent to flank the target installation, situated on a ridge. As orders require, the soldiers maintained large distances between them. Just before arriving at the target and readying for attack, the NCO lost eye contact with Ami. The soldiers called out for him but there was no answer. The NCO radioed me and the exercise had to be halted so that the entire company could search for Ami. He was finally discovered in the branches of an acacia tree observing a troop of ants.’”

He giggled.

“Apparently this happens a lot,” I said. “Udi gives several other examples.”

I picked up another petit beurre and eyed it suspiciously. “I can understand that Udi finds it disturbing that he can’t trust one of his soldiers to stay on course. I don’t need to tell you that if that happened in battle your friends lives would be in danger.”

“It doesn’t happen in battle,” he said.

I didn’t like the way he was looking at me. Like I was a lump of stone. I’ve had lots of soldiers sit across my desk from me and they always give me some consideration. They may like what they see or, and this happens more often, they may not like what they see. But at least they give it some thought. I decided to take off my coat despite the cold. Once, back before I went to officer training, that was the beginning of a brief but deliciously forbidden affair between me and a soldier who wanted a transfer to the brigade supply depot.

“Excuse me, it’s hot in here,” I lied, standing up. I removed the coat slowly and draped it over the back of my chair, keeping an eye on him the whole time. I noticed to my disgust that the buttons in my shirt were straining, but then maybe that would trigger his curiosity about what lay beneath. No, there was no change in his expression. I sat down again and clasped my hands before me.

“Udi writes that it did happen in battle. Just last week,” I said.

He shrugged. “It wasn’t a battle.”

“You were raiding a house in Bil’in in search of a terrorist,” I said. “That’s not a battle situation?”

“The terrorist wasn’t there.”

“As if that matters,” I frowned. Frankly, I was insulted. Not that I really wanted him. He was clearly not my type. Immature, not tall enough. I guessed that his body was not clearly articulated. Maybe he was gay? But Udi’s report seemed to contradict that.

“‘We surrounded the suspect’s house before dawn,’” I read from Udi’s report. “‘The soldier Ami was in the force that broke into the house. We woke the residents, gathered them in the living room, searched the bedrooms and service rooms, but did not find our quarry. The entire operation lasted for no more than fifteen minutes. We then regrouped and exited rapidly, collected the forces that had surrounded the house from outside, and proceeded down the road to where our vehicles waited. At that point I ordered the force to count off and we discovered that number fifteen, Ami, was not with us.’”

This time he frowned.

“They had to go back and get you,” I said.

He was silent, but the idiot’s delight he’d displayed up until now vanished. He wrestled with something inside of him and suddenly looked older and, well, a lot more attractive.

But he remained silent. I shivered and took another sip of my rapidly cooling coffee, and bit into another stale petit beurre, this time noticing a dash of nutmeg, or was it cardamom, that I had missed all these years. Had they always tasted that way?

“Why did they come back?” he finally blurted out. He looked like he was on the verge of tears. “Why did they fucking come back?”

That caught me by surprise. I leaned back in my chair and smoothed my shirt.

“Well, what did you expect them to do?” I asked in astonishment.

“In the bedroom I was sent to search,” he said, “there was a small aquarium, with angel and zebra fish and mollies, and a little castle where a sea god with a trident stood guard.”

He looked into my eyes, but with desperation rather than desire.

“Avi and Efi, who were with me, threw everything out of the closets and the mattresses off the beds,” he said. “But no one was there. They left the room to join the rest of the team in the parlor, and just as Efi was leaving I said I’d be coming in a minute. I don’t know if he heard.”

I suddenly felt that I wanted him very much. I could barely keep myself from reaching out to stroke his cheek.

“I sat down on the bed to watch the fish,” he said, and then explained, “I like to watch fish.”

For some reason I wrote this down on the report in front of me.

“I heard Udi shout an order and the scuffle of the guys rushing out,” he said. “The fish swam, back and forth, caught in their little world.”

I heard the click of his thumb playing with the safety on his rifle. Was he going to do something rash? That had happened once.

“Stop doing that,” I ordered. He stopped.

“Then, maybe a minute later, a girl entered the room. She must have been about sixteen or seventeen. She was dressed the way they dress there, with her head wrapped neatly in soft white fabric, wearing a sort of gray-blue smock-like dress over pants, slender like a young willow. She carried a tray that bore two small tea glasses with gold filigree decoration and a plate of small yellow semolina cakes, each with a pistachio nut at its center. She hesitated, then offered the tray to me. I took a glass of sweet tea and a cake. She lay the tray on the floor, took the second glass of tea, and sat down on the bed beside me. And we watched the fish together, I don’t know for how long. It seemed like forever.”

Now he was smiling again, but it was not a fool’s smile. It was a smile of sorrow.

“And I bit into the semolina cake and it was the most amazing thing I had ever tasted. It was sweet and warm, it played on my tongue and made my soul soar,” he said. “It was like honeydew, or the milk of paradise.”

I lost hope.

“And I wanted nothing more than to sit there for eternity, sipping tea and eating semolina cakes, with this girl beside me, watching her fish,” he said. “I reached to touch her hand but then her mother appeared in the doorway and started shouting something in Arabic. The girl sprang up, spilling her tea and banging the tray against the floor. Some men appeared and began cursing me. I wanted to keep watching the fish but I raised my rifle to protect myself. And then I heard a smash and shouts in the living room and the heavy steps of soldiers. The men in the doorway scattered and I saw Efi look in and shout ‘Here he is!’ And then Udi was there and cursing me even worse than the Arab men had. He grabbed me by the arm like he wanted to tear it off and pulled me out of the room.”

He looked around at the room we sat in, with its metal shelving and black binders, its drab filing cabinet and dingy walls.

“Why did they come back?” he asked again.

I couldn’t help asking, even though I couldn’t believe it was true. “You love her? This—this Arab girl?”

He nodded.

“But you know,” I sighed, “we can’t have soldiers falling in love with girls in the houses they raid. It just won’t work.”

He considered this as if it had not occurred to him before.

“You can understand why Udi and your friends are worried,” I said.

“So I need to stop loving?” he finally said.

I pretended to write something on the report so that I would not have to look at him directly, and suggested: “You need to stop falling in love in dangerous places.”

“I’m going to write here that we talked and that you understand that you need to stop going off on your own,” I said. “I’ll recommend that they give you another chance.”

He nodded.

“And in two weeks you’ll come back and we’ll have another talk,” I said, half-hoping that by then he might be able to see me as he had not seen me today.

“Can I go now?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Find a ride back to your company.”

He got up and hesitated, looking at the plate of petit beurre. I’d gorged so many that only one was left.

“Go ahead, take one,” I smiled.

He reached out broke the lone biscuit in half.

“The other half’s for you,” he smiled.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

More Necessary Stories here!.