Haim Watzman

“You never play your flute anymore.”

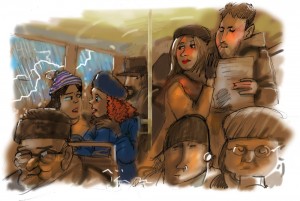

Yael and Aharon squeezed into a corner of the standing area by the rear door of the 34 bus, which smelled of exhaust and wet ponchos. Until last week they had gone down to Ben-Zakkai each Sunday and Wednesday to get the 4 alef to Mt. Scopus but now there was this new line that went to the university from Pierre Koenig Street, closer to home. The people were not the ones they were used to seeing. Bracing himself against the handrail as the bus made a sharp right onto Emek Refa’im, Aharon unshouldered his backpack and opened the zipper, removing a damp copy of an article called “Identity and Freedom” by Amartya Sen, which he should have read over the weekend. The floor was too soaked to put the backpack down and the space too cramped for him to get the straps back over his shoulder, so he wedged it between his back and the window and leaned against it.

illustration by Avi Katz

“You never play the flute anymore,” Yael repeated, looking out at the rain.

The murkiness of the storm-clouded morning was broken by a lightning flash. Yael grabbed his wrist and the article fell to the floor. He cursed under his breath and, apologizing at each stage of descent as he bent down and pushed against the government workers, high schoolers, and nurses who stood around him, picked up the stapled papers, now stained dark with grimy water from umbrellas and boots. The thunder sounded and Yael grabbed his wrist again and put her head on his soggy shoulder.

“Were you talking to me?”

“Who else?” She shivered. “I’m freezing.”

“Is there any particular reason that the subject came up just now?” he asked. “Does it have anything to do with your anatomy exam?”

“The two girls sitting on the seats behind me,” Yael said.

“What about them?”

“Haven’t you been listening? One of them plays the flute.”

“I was reading.”

Yael grimaced and looked out the window again. “So read.”

“I mean, I need to read it for class.”

“Ok,” she said.

He read. “Our religious or civilisational identity may well be very important, but it is one membership among many. The question we have to ask is not whether Islam (or Hinduism or Christianity) is a peace-loving religion or a combative one (‘tell us which it is?’), but how a religious Muslim (or Hindu or Christian) may combine his or her religious beliefs or practices with others.”

“But you don’t.”

He sighed and looked up from the pages. “No time.”

“I liked it.”

“We’re students now. There are things we don’t have time to do. You don’t do everything you used to do, either.”

“Like what?”

He couldn’t think of anything.

Turning to look at him as if the time had come to take stock of the man she had been living with for nearly a year and a half, she reached out and felt the stubble on his face with a damp glove.

“I like it when you have a beard,” she said. “And I like it when you shave. This is neither.”

He took her hand and waited for her to continue, but she didn’t. His eyes wandered back to the article but he it took him a minute to find his place. Then he couldn’t concentrate because the girls on the bench behind Yael were talking.

“You must get that line all the time,” one giggled.

“What? ‘I play the flute, too?’” said the other.

“No guy’s ever tried that one on me.”

“Well, they wouldn’t,” said the flautist.

“‘Would you like to come over and play some duets?’” Her friend mimicked, just short of hysterics.

“What’s so funny?”

“‘Come back to my place and I’ll show you my classical cd collection,’” she continued to mimic. “Did he say that, too? Was he cute?”

The flautist didn’t answer immediately.

“There was something, well, I don’t know, interesting about him.”

“Interesting? You mean he had a good personality? What was he, fat? Cross-eyed?”

“He said he played the flute.”

“Oh, right, the line,” the friend said. “You haven’t changed since high school. When was this?”

“Oh, beginning of last winter. I told you, there was a downpour just when I was getting off the bus and he offered me his umbrella and saw my flute case.”

Aharon tried to focus on the article. “To see the religious or in Huntington’s sense ‘civilisational’ affiliation as an all-engulfing identity is itself a substantial mistake,” he read. But the words didn’t fit together and he had no idea what Sen was saying.

“What was it like?” the friend asked.

“What?” asked the musician.

“His place.”

“Well, it was one of those subdivided apartments around the shuk. A foyer the size of a closet, leading to a tiny kitchen on one side, to his apartment-mate’s room on the other, and to his at the far end. In his room there was a purple beanbag chair missing a lot of beans. A set of wood-plank bookshelves held up by cinderblocks. A mattress on the floor with a rumpled sheet and quilt. A dog-eared Archipenko poster hung on a nail with a clip. Laptop computer and music stand.”

Yael, Aharon saw out of the corner of his eyes, was eyeing the girls sideways.

“To see the religious or in Huntington’s sense ‘civilisational’ affiliation as an all-engulfing identity is itself a substantial mistake,” he read again, trying to put the words together so that they would make sense.

The rain turned suddenly from a normal downpour into a deluge. The bus, which had crept down Emek Refa’im, slowed to a halt just before the old train station. The beating of the drops on the roof sounded like a firing squad.

“So I guess there was nowhere to sit but on the mattress,” giggled the friend.

“No, he brought in two chairs from the kitchen,” the flautist said.

“Ah,” said her friend, who sounded disappointed. “And?”

“We played duets. Some Mozart. Telemann. Kuhlau.”

“And then?”

“He made me some tea and we talked about the Mozart.”

Yael was staring at him now. He looked back at her. She crossed her arms and turned her whole body, still pressed against him, away, toward the cold window.

“And he suggested you spend the night?”

“Well, he did, in fact.” Aharon felt Yael’s body shiver. “And at first I was, well, I didn’t know what to think.”

Her friend sighed.

Yael glared at Aharon. He pretended not to notice. He needed to get the article read.

“So what did you say?”

There was a pause and then the flautist said: “You know me. I always say the wrong thing when it comes to guys.”

“So what was it?”

“I looked around the room and said ‘Here?’”

Yael glared at him. He needed to get the article read.

“‘Here?’” her friend mimicked. “He had his arms around you?”

“No, he was cleaning his flute with an old handkerchief. He pointed out the window and said ‘It’s still pouring and it’s late. You shouldn’t go out.’ Then he went out and knocked on his apartment-mate’s door and came back a minute later with another mattress and a quilt. He asked if I wanted dry clothes to sleep in and apologized for only being able to offer me his spare sweat suit.”

“It must have been raining really hard,” her friend said.

“It was. Like today.”

The bus lurched forward. The volume of the rain was down.

After a minute the flautist’s friend asked: “And he didn’t try anything?”

“Well, I knew he wouldn’t.”

“Your problem,” her friend told her, “is that you don’t have confidence in yourself. Why shouldn’t he want to?”

“Well, between the Telemann and the Kuhlau he told me that he’d met a girl he really liked just a month before. And when he was putting a sheet on the mattress he smiled and said he hoped I wasn’t insulted but he thought that this girl was really serious and he wasn’t going to do anything stupid.”

Aharon let out a deep breath.

“And that’s it?” the friend asked. “So it wasn’t a line? It was for real? About the duets?”

There was no reply at first, but then the flautist said: “If you played Mozart, you’d understand.”

Aharon felt Yael’s hand on his. He looked up at her. Was she crying? Or was it just raindrops from the window?

The friend, who apparently had spent half a minute thinking through the story, said: “I don’t believe you. No guy would do that.”

“And you,” the flautist objected, “think that people are robots who do whatever their instincts tell them to. People are more interesting than that.”

“What are you reading?” Yael asked.

He looked down and pointed to the article.

She took the papers from him and leafed through them. He looked over her shoulder and quickly read the final page as she held it. If he’d read the first and last paragraphs maybe he’d be able to fake understanding what it was all about.

He pointed to the last line.

She read it silently and looked up at him and giggled. “‘The world is richer than that,’” she read out loud.

He looked into her eyes. She looked back. They kept looking until the bus lurched forward.

Yael smiled. “But you really should start playing again.”

Aharon was putting the article in his backpack. “Maybe I will,” he said. “Maybe I will.”

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Lovely. And I just re-read the Bach piece from last year. So thought provoking. Thank you.