Haim Watzman

Elaine had taken the grandkids camping in the cemetery, so Roger was alone for the night. He didn’t like being without Elaine, but he didn’t like having Danny, Aviva, and tiny Gur sleep over either. He was resolved to make good use of the hour or so left before he’d get drowsy and head upstairs to bed.

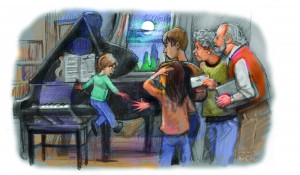

drawing by Avi Katz

A cool breeze from the living room window was blowing on his neck. A nearly full moon was serially obscured and revealed by long, dark clouds that hung low in the sky. He knew this not from looking out the window but from watching the blurred reflection of this celestial game of cat and mouse on the burnished walnut surface of the Steinway baby grand that stood in the far corner of the room, just before it opened into the dining area. The piano was far too big for the space, a fact he had been tactfully reminding Elaine of on and off for the last 23 years, since they moved into this bungalow walking distance from campus. But she would not part with it, and on evenings like this, it was certainly a lovely feature of the room.

He had just opened Karin Rosolio’s article on his ThinkPad when he heard a page turn.

He had a sudden longing for the days when colleagues would send him their writing on newsprint sheets that rustled and cracked when he turned from one to the other. There was something, he felt, about the tactile experience of reading that made it mean more. At least, then he had remembered more of what he read. Although of course he’d been younger, too.

He perused Karin’s opening paragraphs. Since sending her his thoughts (and corrections of no few spelling and grammatical errors) a few days ago, he had been concerned that his reading had been too unfocused and his comments too harsh. They had a long acquaintance; she had been a gracious host during his three trips to Jerusalem over the last ten years. Perhaps the piece was better than his first encounter with the text had led him to believe.

He was just tapping the “page down” button when again he heard a page turn. He glanced up quickly enough to see a leaf of Schumann settle gently against the page that preceded it on the piano’s music rack. Elaine had played something for the children before they left. The breeze was chilly and stronger. Another page flipped. He got up and closed the window behind him, then settled back on the couch with his laptop.

He was just trying to puzzle out a sentence in which Karin seemed to be saying that the meaning of the fragment of text she was analyzing was actually the opposite of what its words clearly stated when the front door pushed open, as with a great effort, and Danny wriggled in between jamb and wood, with wide-eyed Gur on his shoulders. Danny’s just-adolescent chest was heaving and his shirt was streaked with damp. Catching his grandfather’s gaze, Danny pushed the door firmly shut behind him. Out of the corner of his eye, Roger saw a page of Schumann turn. Gur saw it, too, and let out a cry.

“Gur was scared,” Danny said. “He said he saw a man come out of the grave. And then it started raining. So Grandma told me to run back with him. She’ll be here in a minute with Aviva.” Danny then put on a countenance of male pride. “Aviva couldn’t keep up with me even though I was running with Gur and the knapsack on my back.”

Roger glanced out the window and saw thick raindrops splotching the sidewalk. He sighed at an evening of work lost.

“Too bad,” he said. “But I’m sure Grandma has some fun backup idea.”

Danny unloaded Gur, who stood unmoving next to him, staring at the piano. He put his hands up to his ears. Another page of the Schumann turned, which Roger thought was odd, because there was no wind in the room now.

“Come on,” Danny said to Gur. “Let’s go play with your trucks down in the basement.” He tried to take his brother’s hand, but Gur wouldn’t remove his palms from his ears and wouldn’t budge.

“Come on,” Danny said, eyeing Roger. “Grandpa wants to work.”

Roger lay his laptop on the coffee table and got up. He picked up Gur and cuddled him and said “Everything’s fine. You’re home now. But you never got scared at the cemetery before! What happened?”

Gur, whose eyes were on the piano, removed his palms from his ears, pointed at the piano, and said, “It’s too loud.” Then he stuck his index fingers into each earhole.

As the room, now that Danny was breathing normally, was entirely silent, this was incomprehensible. A page of Schumann turned. Rain started drumming on the window.

“Do you mean the rain?” Roger asked.

Gur shook his head slowly, moving it as far left as it would go and as far right.

“The piano,” he said. “Tell the man to stop.”

“What man?” said Danny.

“The man playing the piano,” Gur whimpered.

Danny looked at Roger. Roger looked at Gur. The front door opened.

“I’m soaking wet!” Aviva announced proudly.

“I should have taken an umbrella,” Elaine said, brushing her hands over her gray curls and setting the nylon bag with that held the tent down by the door. “I’m always forgetting to take an umbrella. Aviva, go straight upstairs and take off those wet clothes and get into a hot bath.” Aviva happily complied.

“What’s wrong, Guri?” Elaine asked her youngest grandchild. He refused to look at her.

“He says the piano’s too loud,” Danny giggled. “He sees a man playing the piano.”

“And who is the man playing the piano?” Elaine asked matter-of-factly as she removed her wet running shoes.

“The man who came out of Zayde’s grave,” Gur said.

“He saw a man climb out of your father’s grave,” Elaine told Roger.

“Who would climb out of my father’s grave?” Roger wondered.

“Probably your father. But no one else saw.”

Danny explained. “He said that the man came out of the grave and picked up an envelope from the ground. He opened it and took out some pages and read them. Then he put the pages back in the envelope and put the envelope in his pocket and walked off, the same way we came.”

“Poor kid,” Roger said. “What an imagination!”

“We only noticed that something was wrong when Gur called out ‘You dropped your letter’ and then began crying. That’s when he told us what he saw,” Danny said.

Elaine took Gur from Roger. “And then he insisted that we come home. I tried to talk him out of it but then a few raindrops fell and I saw that it wasn’t in the cards for us to camp out tonight.” She gave Gur a kiss and set him down on the floor.

“Maybe it’s time to choose a different campsite,” Roger suggested hesitantly as Danny glared at him.

“It’s close to home, it’s quiet, and no one bothers us,” Elaine replied tersely. And then, to Gur: “If it’s too loud, go tell him to play more softly.” Gur stared at her with his tarsier eyes, took a deep breath, and turned toward the piano.

“Go on,” she encouraged him. Gur began to walk in deliberately tiny steps.

“The funny thing,” Elaine said, “is that after Danny left with Gur, and I’d finished packing up the tent, I saw this on the grave.” She pulled a damp envelope out of the pocket of her sweatshirt and opened it up. Peering inside, she drew out a torn quarter-sheet of stationery, then a handful of pieces and shreds. “It’s a woman’s handwriting—look how thin and graceful the penmanship is. But I can barely make anything out.”

Gur had reached the piano bench. “Softer!” he commanded.

“And look at this stamp on the envelope! Arabic on the top and Hebrew on the bottom. ‘Palestine’ in the middle.”

Roger took the envelope and looked at it. He glanced at the tattered paper in Elaine’s hand, spotting a tremulous underlined word, “love.”

Gur giggled, clapping his hand to his neck as if he were being tickled.

“It must be from the time your father spent there,” Elaine said.

Suddenly their eyes were caught by Gur, who was rising up in the air. At about five feet off the floor he threw his hands out and arched them as if he were hugging someone’s neck. He descended slowly and settled on his feet on the piano bench. He listened to something and then nodded. Looking into the eyes of the great-grandfather only he could see, he reached out, turned a page of Schumann, and waited patiently for his next cue.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

More Necessary Stories!

Beautiful writing!