Haim Watzman

The Jerusalem winter that kept coming back had finally come to an end, or perhaps it was just taking another break. Whatever the case, the clouds had gone from dark and low to scattered and high, the wind had slowed from gale force to tickle, and the temperature had risen from ski gear to light jacket. It was the first Shabbat in weeks that you could go out without an umbrella. Ori and Dudi had gone to play with friends, so Ronen and Gali grabbed the opportunity.

“It’s too cold,” Gali objected. She was half-reclining on their couch, being kicked from inside.

“But it’s warm today!”

“It’s still cold.”

“We haven’t been there for months.”

“No one goes there anymore. It’s like a ghost town. It gives me the creeps.”

“Well, then,” Ronen asked, “where should we go?”

“You know I hate making decisions.” She took Ronen’s extended hand and allowed herself to be pulled up slowly, so that she could keep her balance. “Why can’t you make up your mind?”

Since they had been married for nearly eight years, nothing in the previous exchange really meant anything.

In 1968, Israel’s Own Lawyer Told It That Razing Suspects’ Homes Is Illegal

My new column is up at Haaretz:

It was March 1968. Yaakov Herzog, director-general of the Prime Minister’s Office, received a memo marked “Top Secret” from the Foreign Ministry’s legal adviser, Theodor Meron. As the government’s authority on international law, Meron was responding to questions put to him about the legality of demolishing the homes of terror suspects in East Jerusalem and the West Bank and of deporting residents on security grounds.

His answer: Both measures violated the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention on the protection of civilians in war. The government’s justifications of the measures – that they were permitted under British emergency regulations still in force, or that the West Bank wasn’t occupied territory – might have value for hasbara, public diplomacy, but were legally unconvincing.

The legal adviser’s stance in 1968 is important today precisely because it is unexceptional. It’s the view of nearly all scholars of international law, including prominent Israeli experts.

What the Breaking the Silence Report Says about the Gaza War–and Doesn’t

Excerpt from my new op-ed in The Forward In its most recent report , Breaking the Silence does something different — it points its spotlight at the haze of a full-scale military operation, last summer’s Protective Edge incursion into the Gaza Strip and tries to draw from its testimonies bigger lessons about an Israeli army … Read more

16 Million Refugees Are Not Some Other Country’s Problem

My new column is up at The American Prospect:

Item: Two Eritrean refugees who reached Israel by crossing the Sinai desert went to court Thursday, asking for an injunction preventing the government from deporting them to Rwanda. The policy of forced deportation is new, but a recent report by Israeli refugee-rights organizations shows that in case after case, Sudanese and Eritrean asylum-seekers who supposedly left voluntarily in 2013-2014 did so under pressure, including threats of indefinite detention. Those sent to Rwanda were in turn expelled by authorities there almost immediately. Others were sent back to Sudan, where some were imprisoned and tortured for the crime of visiting an enemy state—Israel. Dozens of refugees who “voluntarily” left Israel for Africa are now trying to reach Europe: by land to Libya, then across the Mediterranean on smugglers’ boats.

Item: An Australian lawyer has filed suit against that country’s government to keep it from returning the family of a five-year-old Iranian refugee girl from a detention center in Darwin, on Australia’s northern coast, to the island country of Nauru—a speck of land halfway to Hawaii. Australia pays Nauru to take boat people caught at sea while trying to reach Australia. The girl’s family was brought to Darwin because her father needed medical treatment there. She is suffering post-traumatic stress from the time she has already spent in a detention camp on the island.

Item: When a smuggler’s boat crashed against rocks on the shoreline of the Greek island of Rhodes last week,

You can take the Jews out of exile, but you can’t take the exile out of the Israeli right

My Yom Ha’atzma’ut column is up at Haaretz:

I’m sitting in a cafe in Jerusalem almost on the eve of Independence Day, listening to the Ashkenazi and the Ethiopian waiters joking in Hebrew, in circumstances that existentially are a billion miles from anywhere that my great-grandfather in the Ukraine could have imagined a descendant living, and I’m thinking about the speeches that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will give over the next couple of days – and thinking that he actually does not get that we are independent. Not that I mean to pick on Netanyahu, except as a personification of the Israeli right, which for all that it sees itself as strutting in Jabotinskian pride and glory, does not understand what it means to be here – physically, culturally or morally.

It’s a reasonable bet that in one or more speeches Netanyahu will mention Iran, the perfidy of Western nations, our isolation, and our potential extermination. Last week on Holocaust Remembrance Day, Netanyahu gave a speech that was more about Iran and fear of a new Holocaust than honoring the memories of those who died in the actual Holocaust. Netanyahu’s entire public career consists of pronouncements that it is, right now, 1938, if not August 1939. His forecasts are detached from the physical universe but are wired directly into the neurons of enough of the electorate to win him elections.

For the literarily or religiously inclined, the words that best portray his constant mood are, “The life you face shall be precarious; you shall be in terror, night and day, with no assurance of survival.”

Fireflies — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

Fireflies, forgotten for many years, reappear one summer evening.

Shabbat, Riverside Park, along the Hudson. Under the shelter of tall trees, runners race by. Couples stroll, families with small children sprawl on the grass. The first flashes, as the sun drops low over New Jersey, catch me by surprise. Then the tears begin.

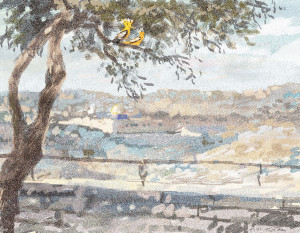

illustration by Avi Katz

It is like a dream. Niot’s look of pure delight and wonder when he sees fireflies for the first time. He is twelve years old, or perhaps ten. We are in Silver Spring, at my parents’ home. I am sitting in an armchair reading a newspaper. Twilight falls. Niot appears behind the frame of the large sliding glass door that separates the family room from the backyard. He catches my eye, then turns his gaze to the yard. Points of weightless brilliance as day slides into night.

“Specks of living light / twinkling in the dark,” Tagore calls them. The picture is clear and present to me in the park at dusk, as clear as if I were again in that armchair and Niot beyond the sliding door.

When Niot first began to appear in my dreams, he was far away, visible for an instant, then gone. I wept in my sleep.

How could light make me cry? How could a creature showing itself to the world make me feel that world as empty? The firefly’s light is a cold light. It startles but it does not warm.

Winged embers mark trails along the river, like comets flying close to the sun, tails aimed at me.

Eulogy for Niot by his Brother, Asor– Four Years — הספד לנאות מאת אחיו עשור אחרי ארבע שנים

Asor Watzman

גרסת המקור בעברית למטה

For that reason, I want to share with you some memories I have of Niot. I will do that using a story from the Talmud:

Rabba bar bar Hanna said: When Rabbi Eliezer fell ill, his students came to visit him.

Eulogy for Niot — Four Years — הספד לנאות אחרי ארבע שנים

גרסת המקור בעברית למטה

Niot:

On Sunday I found comfort, as I often do, in music. I listened to Franz Schubert’s piano sonata in B flat major, a work he wrote just before his death at a young age. At the end of the sonata Schubert placed a measure with a whole rest. In other words, the pianist plays the final notes, which come at a dizzying, furious pace, and then, according to the composer’s instructions, there is a moment of silence before the performance is really over. Perhaps Schubert intended for the pianist to remain with his hands in the air as the sonata echoes through the room.

On Sunday I found comfort, as I often do, in music. I listened to Franz Schubert’s piano sonata in B flat major, a work he wrote just before his death at a young age. At the end of the sonata Schubert placed a measure with a whole rest. In other words, the pianist plays the final notes, which come at a dizzying, furious pace, and then, according to the composer’s instructions, there is a moment of silence before the performance is really over. Perhaps Schubert intended for the pianist to remain with his hands in the air as the sonata echoes through the room.That same evening your friends came to visit us. Two of your wonderful teachers, Gabi and Re’em, joined them. At the end of the evening Gabi said that he still hears your voice. Re’em said that he still hears your laugh. I related dreams in which you have appeared, sometimes so close that I can touch you, sometimes beyond my reach.

Peripheral Vision

In an earlier age, perhaps, privacy would have won out, but in an earlier age he would not be gazing at a photograph of his girlfriend on an electronic device in the crowded waiting room of the Terem all-night emergency clinic in Talpiot. Were he, say, a member of Trumpeldor’s Labor Brigades back in pioneering days, one who had been taken on muleback to a doctor’s home in Yavna’el (had it been founded then?), because of, say, a burn on his shin from a misaimed bucket of hot asphalt, he would have had to conjure up Yael’s bare limbs in his mind’s eye and no one would have been able to peek. That body would have been his alone to see. But then no one else would know what a treasure he had and, face it, part of the enjoyment of a treasure is the admiration of those who don’t have it.

But it took only a fraction of a second for his peripheral vision to make out that the invasive but welcome gaze came from the eye of a small person dressed in a long-sleeve shirt, plaid with very wide blue stripes, tucked into brown corduroy trousers with an elastic waist. Above the eye was a black velvet kipah, and the head to which it belonged leaned lightly and lovingly on the forearm of a lean and tall man in a black suit and clipped beard with an open book on his lap from which he was reading to his son.

The boy dutifully turned his eyes to the book, but not for long. Hanan gave him a smile. The boy shifted in his chair and smiled cautiously.

“Tomorrow this sign shall come to pass,” the father intoned, pointing to the page and glancing at his son. “The Ben Ish Hai is talking here about a verse from the story of the plagues in Egypt. But we know that the word ‘sign’ doesn’t have to be a bad thing, a bunch of flies that got in the Egyptians’ beds and food and noses. A sign is also the mitzvot, the commandments that God has given the Jews, which are a sign of the covenant between the Holy One, Blessed be He, and his people.” And he explained how if you rearrange the Hebrew letters of the word “tomorrow,” which are MHR, you get RMH, which is the number 248, which is the number of limbs and organs of the human body, and also the number of positive injunctions in the Torah.

“How do we know there are that many?” the boy asked his father.

“We can count them in the Torah, like our Sages did,” the father replied.

“No, I mean the parts of the body.”

“Well, if you look at a person’s body, if you could see everything about it, you could count that many,” he explained.

“Let’s count,” said the boy, pointing to the photograph on Hanan’s phone.

Niot and the Niot Project — Update, Pesach 2015

Dear friends, This coming Friday night we will sit down to our Seder, once more without our son Niot. Four years ago, the Seder was our last night together with him. He died a few days later, in the middle of the Pesach holiday, and we miss him very much. A number of memorial events … Read more

The Question of Questions

Haim Watzman

Seder night four years ago was my last night with my younger son, Niot, who died in a diving accident a few days later. Each year I write a dvar Torah for “Shabbat Shalom,” the weekly Torah portion sheet published by Oz VeShalom-Netivot Shalom. The Hebrew version can be found here.

The Four Questions appear in the Hagadah as a preface to the Maggid, the telling of the Pesach story. They stand as prototypes of the questions that are meant to be asked during the entire Seder night. The evening’s unusual observances are intended, in part, to elicit questions, especially from the young people sitting around the table.

Some two decades ago, when my children were small, I was able to observe any number of times how effective this strategy is. One year we decided to adopt a custom with its source in the Talmud—to clear the table of the Pesach plate and matzot immediately after yahatz, the breaking of the middle matzah. The source of the custom comes from the school of Rabbi Yanai: “Why is the table cleared? Said the school of Rabbi Yanai: so that the children will see it and ask [why].” At that Seder, my younger son, Niot, who was preoccupied with his own affairs during the previous stages of Kadesh, Urhatz, Karpas, and Yahatz, suddenly noticed that something was happening and asked in a loud voice: “Why are you doing that?” By asking a spontaneous question, he had fulfilled his duty and we thus did not require him to chant the official Four Questions, an honor he happily passed on to someone else.

Niot’s question is, in fact, the question of questions, and is a much harder one to answer than the prescribed kushiyot.

Until You Don’t Know — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

Jerusalem is a cipher; Jerusalem under snow is a cipher erased.

The high priestess of a god whose name I didn’t quite catch offers me a cardboard cup of spiced wine. Her bare arms are goosebumped from the cold and her cheeks flushed from the wine. I think I am in love with her but, given my luck, her cult no doubt requires her to be virginal. The pope breezes by and his vestments unfurl against my hand, spilling the wine over the high priestess’s crescent scepter, or perhaps it is a scythe. She smiles, but fire flashes from her eyes, and she turns away.

“Rabbanit Kappah,” says a woman, one of a group of three, in Golda shoes and with a kerchief tied tightly over her head. She is the one who took my coat at the door, so I presume she is a hostess. She reaches out and touches my elbow lightly, as if she wants to touch more.