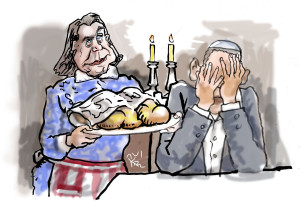

Barak and Bona Washingtonia are one of those couples who have grown apart over the years. Barak’s an army buddy of mine, a regular guy, and at least from my point of view he’s as great as he always was. Bona, who’s an old friend of Ilana’s used to be a lot of fun, too, but in recent years she’s drifted into this weird hypernationalist New-Agey Breslov stuff and it’s been a strain for Barak. More than a strain. The poor guy is having a real tough time, especially now that the kids are all out of the house.

So when he invited me and Ilana over for Friday night dinner, we felt a special duty to go, even though it was freezing outside and we really felt like staying in. It’s a mitzvah to make peace in the home, between husband and wife, and all the more so on Shabbat.

“Hey, what’s eating you, ahi?” I said. “Here, let’s sit down. Don’t keep it in. Let it out. Lay it on me.”

He clenched his fists and hissed and covered his face with his hands and leaned back and looked at the ceiling and finally said, “I can’t believe she invited him!”

“What do you mean? Who?” I asked. “Hey, should I get you a drink of water? A beer?”

I could hear animated conversation in the kitchen. It didn’t sound like Bona was upset. In fact, she called out in her singsong voice: “We’ll just be a few minutes. We’re waiting for a very special guest!”

Barak took a big breath and finally got it out.

“Bibi!” he sizzled.

Why Israel’s Crazy Electoral System Might Be Best Idea Ever

Haim Watzman My piece praising Israel’s proportional electoral system is now up on the Forward’s website. Jewish suffragettes scored a signal achievement in 1920, when the first nationwide elections were held in the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine. They received 600 votes. This smattering of women — we may presume that nearly all of … Read more

Cloudburst — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

The man who grunted into a chair at the table next to me at Aroma Sokolov had fleshy overworked fingers with hair thicker than he had on his head. A tan sweater, a size too tight for him, outlined the bulge of his belly, and his eyes and nose were watery from the droplets of exhaust that shiver in the air on a Holon winter morning. He unfolded his free copy of Yisra’el Hayom and, in response to a query from a young man at the counter, held up two of those fingers. He flipped the paper to look at the forecast, shook his head, settled back in his chair, and addressed me.

I nodded and gave him a smile with which I tried to say “You know it!” And also “I’m kind of busy so leave me alone.”

“But that cloudburst last night? Did you catch it? At two in the morning?”

When I didn’t respond, he nodded in the direction of the counter. “That’s my son, Niv. He’s getting married next week.”

“Mazal tov,” I said, without an exclamation point.

“He’s a good kid. Great girl, too.” Niv, drumming a riff on the counter while he waited, had a runner’s build and a frazzle of rusty hair.

“Looks it,” I said, keeping my eyes on my laptop screen.

He gave up and returned to the newspaper. “Niv!” said a loudspeaker voice and a minute later the son placed a tray on the table and sat down. He carefully, respectfully lifted a glass mug of kafe hafukh from the bright orange tray and put it in front of his father, followed by a small plate bearing a jelly donut and two tiny metal jugs of hot milk. Tearing a packet of sugar with his teeth, he sweetened his own hafukh, which remained on the tray. From a pants pocket he drew an iPhone and positioned it next to the coffee. The two of them sipped silently, long enough for me to get focused and forget they were there.

“Did you catch that cloudburst at two a.m.?” the father suddenly said.

The Last War But One — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Abba was fanning himself with the folded front section of Ma’ariv when the bell buzzed. Ema was making her way through the kitchen door with a transparent tumbler of tea and nana, held on a waxy serviette, stirring up settled sugar. Abba looked up at her. Ema reached the couch, placed the serviette on the glass top of the coffee table, gently settled her tumbler on the serviette, and seated herself, with dignity, on the settee. She picked up the weekend supplement and considered the table of contents. The doorbell, whose chime had long since deteriorated into a scratchy drone, sounded again, much longer.

He turned his gaze to me, sitting on the cool patterned tiles with my Ditza.

“Is someone going to get the door?” he asked, directing his words into the high-ceilinged vacuum, the drop of sweat falling from his cheek and just missing the strap of his white singlet to hit a tuft of hairs on his bony shoulder.

Ema finished reading a sentence, smiled, and slowly, with poise, directed her eyes at her husband.

“Well, you certainly don’t expect the girl to do it,” she said acidly.

The Gollux and the Clockmaker: An Appreciation of Paul Harding’s Tinkers

Presented at my book club, Dec. 2, 2014

Shop Indie Bookstores

Once upon a time, in a gloomy castle on a lonely hill, where there were thirteen clocks that wouldn’t go, there lived a cold, aggressive Duke, and his niece, the Princess Saralinda. She was warm in every wind and weather, but he was always cold. His hands were as cold as his smile and almost as cold as his heart. He wore gloves when he was asleep, and he wore gloves when he was awake, which made it difficult for him to pick up pins or coins or the kernels of nuts, or to tear the wings from nightingales. He was six feet four, and forty-six, and even colder than he thought he was. One eye wore a velvet patch; the other glittered through a monocle, which made half his body seem closer to you than the other half. He had lost one eye when he was twelve, for he was fond of peering into nests and lairs in search of birds and animals to maul. One afternoon, a mother shrike had mauled him first. His nights were spent in evil dreams, and his days were given to wicked schemes.

Wickedly scheming, he would limp and cackle through the cold corridors of the castle, planning new impossible feats for the suitors of Saralinda to perform. He did not wish to give her hand in marriage, since her hand was the only warm hand in the castle. Even the hands of his watch and the hands of all the thirteen clocks were frozen. They had all frozen at the same time, on a snowy night, seven years before, and after that it was always ten minutes to five in the castle. Travelers and mariners would look up at the gloomy castle on the lonely hill and say, “Time lies frozen there. It’s always Then. It’s never Now.”

The cold Duke was afraid of Now, for Now has warmth and urgency, and Then is dead and buried. Now might bring a certain knight of gay and shining courage – “But, no!” the cold Duke muttered. “The Prince will break himself against a new and awful labor: a place too high to reach, a thing to far to find, a burden too heavy to lift.” The Duke was afraid of Now, but he tampered with the clocks to see if they would go, out of a strange perversity, praying that they wouldn’t.

Tinkers and tinkerers and a few wizards who happened by tried to start the clocks with tools or magic words, or by shaking them and cursing, but nothing whirred or ticked. The clocks were dead, and in the end, brooding on it, the Duke decided he had murdered time, slain it with his sword, and wiped his bloody blade upon its beard and left it lying there, its springs uncoiled and sprawling, its pendulum disintegrating.

In Tinkers, Paul Harding offers us the oldest kind of story known to humankind, a myth, or fairy tale, constructed out of many of the same elements as James Thurber’s The Thirteen Clocks. It’s the oldest kind of story because it is the kind of story we most need. It plumbs depths that naturalistic fiction never reaches; it challenges our feeble attempts to explain and understand the world in which we live and the people we love.

Not Just an Election Pretext: The Nation-State Law is Netanyahuism

My new column at The American Prospect, explaining the political crisis over the nation-state law, went up a few hours before Benjamin Netanyahu announced new elections:

Israel’s government is on the edge of collapse. The prime minister and senior cabinet members are trading insults as if they are already campaigning against each other. OK, that’s fairly normal. Israeli coalitions are unstable partnerships of enemies. When they can’t compromise on an unavoidable issue—the budget, for instance, or peace talks—they threaten each other with going back to the voters. Sometimes threats become reality.

What’s abnormal is that for the past week Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has seemed determined to scuttle his current coalition of the right and center over an entirely avoidable crisis: his desire to pass a law constitutionally defining Israel as the nation-state of the Jews. His centrist partners see the law, correctly, as an assault on democracy. The law will inflame tensions with the Arab minority, and damage Israel’s already poor international standing.

Why go to the trouble? Over three-quarters of Israel’s citizens are Jews, who quintessentially display their Jewishness by arguing constantly about what “Jewish” means. Public life is conducted in Hebrew; schools and offices shut for Passover and Rosh Hashanah. The crisis looks so unnecessary that pundits have suggested that it’s a pretext: Netanyahu has decided that he’ll do better in elections now than later, and believes that the nation-state law will allow him to run as the candidate of patriotism.

This Machiavellian explanation is too kind. The bill is Netanyahu-ist, and that’s what really is frightening.

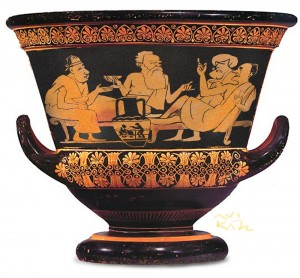

Socrates and Semites — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

I went down yesterday to the Piraeus, in mind to attend the new drama by Adamschylus at the Zeatropolitan, of which everyone in the Agora is speaking. In truth, at our age, the wife and I seldom attend performances at the Zeatropolitan, preferring rather to watch the simulcast at the Stoa of Attalos, but Abefoxmachus, president of the tribe of Semitikropis, had objected and, holding his breath until his face turned blue, had persuaded Gelbus, director of the Zeatropolitan, to replace the broadcast of the new production with a screening of Exodus, which I have seen all too many times.

I went down yesterday to the Piraeus, in mind to attend the new drama by Adamschylus at the Zeatropolitan, of which everyone in the Agora is speaking. In truth, at our age, the wife and I seldom attend performances at the Zeatropolitan, preferring rather to watch the simulcast at the Stoa of Attalos, but Abefoxmachus, president of the tribe of Semitikropis, had objected and, holding his breath until his face turned blue, had persuaded Gelbus, director of the Zeatropolitan, to replace the broadcast of the new production with a screening of Exodus, which I have seen all too many times.

I had just reached the half-price ticket booth by the customs house when Taruskinus chanced to catch sight of me from a distance, and told his servant to run and bid me wait for him. The boy ran up to me and grabbed my cloak from behind, and said: Socrates, Taruskinus is approaching and desires you to wait.

“I certainly will,” I said.

“I perceive,” Taruskinus said to me when he arrived, “that the wisest man in Athens intends to attend the theater this evening.”

“I know not what the wisest man in Athens may be doing,” I said, “but as for me, yes, I have in mind to attend a performance of Adamshylus’s new drama.”

“I believe,” Taruskinus replied, “that you mean that anti-Semitikropic work Davidipus Rex.”

Rescue — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

My brother Levi says that if I weren’t a woman he’d kill me. Just like the Arabs.

The reason he kills Arabs is that they are evil and kill us. He doesn’t kill his sister because because, he says, women think with their hearts and not their minds. Because they see only the here and now and not history. Because they trust too much.

drawing by Avi Katz

So, he said, I will spare you and let the Holy One, Blessed Be He punish you. That Arab could have killed you. Or worse. With you alone in the house. But now everyone in Meah She’arim knows. Soon you’ll be called to testify in their courts and the whole Yishuv will learn of your shame. Perhaps that is the punishment that your life has been spared to receive.

As the summer of the year that the English call 1929 wanes, I ask you, My Rock and My Savior, is this so? More than seven weeks have passed since that Friday and Shabbat of slaughter and fear. So many of your people died. And I saved none of them. Instead, I rescued an Arab.

One City, Divided

My cover story in the National Journal on Jerusalem is up:

On a midsummer afternoon, at the King George Street station in the center of downtown Jewish Jerusalem, I boarded one of the silver four-car trams of Jerusalem’s only light-rail line. The electric train swooshed east along Jaffa Road to the City Hall stop, just before the narrow, now-unmarked no-man’s-land that divided the city before 1967. The next stop was the Damascus Gate station, serving downtown Arab Jerusalem. From there the train headed north toward outlying Palestinian and Jewish neighborhoods.

It was a normal rush-hour trip—except that there were no Palestinians on the train. No father spoke Arabic to the son sitting next to him; no teenage girls chattered in Arabic about their purchases on Jaffa Road. The women who wore head scarves had them tied behind their necks, Orthodox Jewish style, not wrapped under their chins, Muslim style. No one got on or off at Damascus Gate. In the Palestinian neighborhood of Shuafat, a mourning banner with a huge picture of murdered Arab teenager Muhammad Abu Khdeir hung from an apartment building facing the tracks. A sign on the ticket machine on the platform said it was out of order—as it has been since angry young residents smashed it during the violent protests that followed the murder of Abu Khdeir at the beginning of July. No one got off there or at Beit Hanina, the northernmost Palestinian neighborhood on the line.

The missing passengers weren’t participating in an organized boycott. They were simply afraid.

Comfort from Calvin — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

I did not want to be on the plane I boarded in mid-July. I’ve been through a lot of wars, but this is the first one I was leaving the country for. How could I? I had two children in active service—a son who’s a special forces officer and a daughter in a combat infantry unit. The wonderful woman that my son was scheduled to marry in just weeks, herself an intelligence officer, had been called up as a reservist. Twice in the previous week sirens had gone off in Jerusalem as Hamas launched long-rage rockets in our direction.

drawing by Avi Katz

But tickets for the trip, for a visit to Dad and Mom in Denver and a literary conference in New York, had long since been purchased, and Ilana insisted that I not change my plans. “It’s not as if by being here you could change anything,” she pointed out.

Ilana’s admonishment was more pregnant than she realized. For Israelis like me, loyal Zionists who have for decades spoken out for Israeli democracy, tolerance, and accommodation with the Palestinians, the Gaza War was triply depressing. We, our family, our friends, and our country are under attack and our soldiers and civilians are being killed. Israeli bombs have killed hundreds of people in the Gaza Strip, embittering a Palestinian population with whom we must find a way to live. But, no less worse, death and destruction are turning the people on both sides ever farther away from accommodation and mutual understanding. Should we give up? Are we really impotent when it comes to peace?

The power to change, the refusal to accept the world as it is and the impulse to make it better, is fundamental to Judaism. The concept of free will is built into the Jewish Bible and into the wisdom of rabbinic literature, the building block of the ethical systems of nearly all Jewish theologians and philosophers throughout the ages. Not only can we change ourselves and determine our own actions, we believe, but we can also, through our actions and words, cause other people to change the way they act and think.

How ironic, then, to find myself seated on the plane next to a Calvinist.

It’s Not About Tunnels. So What Is the Gaza Conflict About?

My new column is up at The American Prospect. Since the article went up last night, Hamas rejected extending the ceasefire and resumed rocket fire less than one minute after it ended. Israel has resumed missile and artillery fire. Alas.

I.

At four o’clock after the war—which is to say, 4 p.m. Tuesday—a Hebrew news site carried a telegraphic bulletin: The head of the Israeli army’s Southern Command announced that residents of the area bordering Gaza could return to their homes and feel safe. The reassuring message was undercut by the bulletin that appeared on the same site one minute earlier: “IDF assessment: Hamas still has at least two to three tunnels reaching into Israel.”

At the end, if Gaza War of 2014 has ended, if the ceasefire holds, it was about tunnels—some as deep as forty meters (130 feet) below the surface, dug from inside the Gaza Strip and reaching hundreds of meters into Israel, into farming villages and to the edge of the town of Sderot —tunnels from which Hamas fighters could suddenly surface to attack civilians or soldiers. To be precise, this is how the war is most immediately remembered in Israel: as an offensive aimed at removing the subterranean threat. In the rubble of Gaza, where nearly 1,900 people were killed by Israeli fire, where 460,000 are homeless, the presumed purpose of the war will surely be remembered very differently.

Let’s return, though, to the Israeli perception: People remember backwards, viewing earlier events through the lens of later ones. The Israeli government’s announced goal in fighting since the ground invasion of Gaza on July 17 was finding and destroying attack tunnels. This, therefore, is remembered as an original purpose of the war. A friend, left of center politically, asked me the afternoon after the war why Israel had earlier accepted an Egyptian proposal for a ceasefire that was set to start before the ground invasion, since the government obviously knew it would need to invade Gaza to get rid of the tunnels.

But the crisis wasn’t about tunnels when it started. The Israeli government’s tactical goals shifted repeatedly. At no point, it appears, has Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had a strategic political vision. Yet the story of the tunnels leads inevitably to the need for a political resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

This Is Your Brain On War

My new column is up at The American Prospect:

As I write, the livestream from Gaza of news about death continues. If I give a casualty count, it may be outdated before I finish typing it. It won’t include those Palestinians—civilians and Hamas fighters—who may be buried in rubble in the Sajaiya neighborhood of Gaza City, which the Israeli army has invaded in search of rockets and of tunnels leading into Israel. Nor will it include recent deaths of Israeli soldiers; the military often delays such announcements for hours. Collapsing under the weight of the Gaza reports is whatever initial support Israel had in the West as its cities came under rocket fire. The same reports have fed criticism of Hamas in the Arab world.

he war isn’t a hurricane; it didn’t happen by itself. Leaders on both sides made choices. In Israel, despite an unusual number of protests so early in a war, most of the public seems to think the government is doing the right thing, perhaps too timidly. I doubt anyone can judge public opinion accurately amid the chaos and fear in Gaza, but credible estimations are that support for the Hamas government rises in proportion to Israeli attacks.

Maybe just to keep my own sanity, I have to ask: How do leaders believe that such flawed decisions were the only reasonable choices? How can masses of people keep supporting those policies even as they prove disastrous? What’s wrong with our heads? By that I mean not just the heads of Israelis and Palestinians but of human beings, since I don’t have any cause to think that the sides in this conflict are being uniquely irrational.