Haim Watzman

“America is lucky,” he says as he smooths his hair and slaps his cheeks lightly. “To have Trump, I mean.”

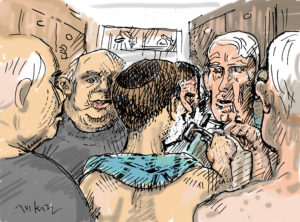

But maybe I’m wrong. Bashan’s reverse image moves into my field of view just as I offer a weak smile and start on the stubble on the left side of my face.

“Right.” Bashan grimaces at his reflection. Where Lerner is steely, he is malleable; where Lerner has angles, he has arcs. A lot less hair, too, on his head, that is. Still, he must have been a looker back in the 1948 war, when they conquered the Negev together. Bashan had been a platoon commander in the Palmach’s Yiftah Brigade and Lerner one of his soldiers. I’d heard about it time and again in the shower.

“In our day,” Lerner’s reflection says as it adjusts the shoulders of its backward t-shirt, “the world had strong leaders who stood up for their countries. Churchill. De Gaulle. Roosevelt. Ben-Gurion.”

Bashan’s reflection leans forward at me and wiped a grain from its eye. “The Old Man.”

democracy

Advice to Dissent

Israelis often wail that the country lacks unity. But when most Israelis say “We need more unity,” what they really mean is “More people should agree with me.” Dissent can be a pain, but it’s essential—as is recognized by the Sages of the Talmud in the Horayot Tractate (4b). The Beit Midrash run for the last two years by Kehilat Yedidya last week finished its study of this tractate with just this insight.

Horayot deals with the issue of what happens when a court—a rabbinic court, which served as the chief legislative and moral authority of Jewish communities in Talmudic times—makes a ruling mistakenly. To do this, it reads Torah passages in Leviticus 4 and Numbers 16. These passages deal with a sacrifice called the korban shogeg, to be offered by a person or group of people who has violated a Torah precept without intention. While the Sages of the Talmud lived long after the Temple was destroyed and the sacrificial service ceased, they continue to use this language. Assignment of responsibility for the error is designated by the assignment of the requirement to bring this sacrifice.

The question is: if a court makes a ruling that violates the Torah, does the ultimate responsibility fall on the court, or on the individual who obeyed the court’s instruction?

Rachel as a Metaphor–Why Israeli Democracy is Just as Bad/Good as All Others

In politics, the pure is the enemy of the good. One need look no further than the discussion that ensued in response to my post Votes Are Not Enough. Some of the most prolific correspondents there, coming from both the right and left, shared the implicit assumption that democracy, if not pure, is not democracy.

Unfortunately, they won’t be able to read the fine essay that Nurit Gretz published in the arts and literature section of Friday’s Ha’aretz—the piece, in Hebrew, seems not to be available on-line. Gretz addresses a problem of the same genre and in doing so shows how wrong purism can be.

She does so by writing about one of the icons of Labor Zionism, A.D. Gordon, the Second Aliya’s guru of back-to-the-earth socialist egalitarianism. One of Gordon’s disciples was the poetess Rachel Bluwstein, who lived and worked at Kevutzat Kinneret on the southern edge of the Sea of Galilee, where Zionist farmers first tried to work on a communal basis. Bluwstein—universally known in Israel today as Rachel the Poetess—lived in accordance with Gordon’s teachings. She abandoned the middle-class life she’d known in Russia and set aside her aspirations for education and culture to become a simple farmer.

Knowledge and the Public Good–Some Suggested Reading

The dissemination of knowledge-high-quality knowledge-is essential to a democratic society. So I’d like to point out an interesting juxtaposition of articles from my Shabbat reading that, taken together, have something important to say about the importance of getting good knowledge to the public.

Danielle Allen’s review of Josiah Ober’s book Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens in The New Republic concludes:

Josiah Ober shows us that Athens knew what the Athenians knew, because the city as a whole had devised institutions that made sure the useful knowledge of the widest possible range of individuals flowed to where it was needed. Have we fully tapped into the resources of participatory democracy to supplement our own representative structures with a citizenry within which all the sluices of knowledge are open and have been set a-flowing? Does America know what Americans know?

In the March 5 issue of Nature, Harry Collins, a social scientist who studies science, concludes an essay entitled “We Cannot Live By Skepticism Alone” with these words:

Science, then, can provide us with a set of values-not findings-for how to run our lives, and that includes our social and political lives. But it can do this only if we accept that assessing scientific findings is a far more difficult task than was once believed, and that those findings do not lead straight to political conclusions. Scientists can guide us only by admitting their weaknesses, and, concomitantly, when we outsiders judge scientists, we must do it not to the standard of truth, but to the much softer standard of expertise.

Let Them Rage: Why Anti-Zionists Should Be Allowed to Run

Haim Watzman If it weren’t the fact that the fracas at yesterday’s meeting of Israel’s Central Election Committee was theater rather than serious deliberation, I might be more upset about the decision to bar from contesting the coming election two of the three Arab slates represented in the current Knesset. Everyone there, both the right-wingers … Read more

Oh, For the Days of the Party Boss and the Back-Room Deal!

There was a membership meeting at shul Saturday night to discuss plans to finish our building’s unfinished basement. A well-meaning, socially-concerned member (true, those labels apply to pretty much everyone in Kehilat Yedidya ) suggested that democratic procedures required that we poll the entire community, asking each and every member whether they favor or oppose the proposal.

If you’ve ever been involved in synagogue governance, or served on a PTA board, or tried to run any other organization, no matter how mundane, you’ll know why I started turning red. You work together with other concerned members and, through a process of study and deliberation, weigh various options, compromise between opposing views, and put together the best plan you can. Then you bring it before the membership and everyone becomes a partisan and wants to go back to square one. If the meeting isn’t well-managed, all your work is for naught.

How anti-democratic of me! I’ve been accused of precisely such dictatorial tendencies on several occasions during my life. But my socially-concerned, democratically-committed fellow-Yedidyan was wrong. In properly-functioning democracies, not everyone gets to decide everything. And an overdose of public involvement can in fact subvert true democratic process. It’s just such a surfeit of democratic politics that has turned Israel into a nearly non-functioning democracy in recent years, and led to a situation where Israelis will be presented in February with a choice of notably mediocre candidates for its legislature.

Tough Love: Israel And Its Army

Big news: public trust in the Israel Defense Forces dropped a full three percentage points in the last year. Now only 71 percent of Israelis (all Israelis, including non-Jews) trust their army, as opposed to 74 percent last year. The figures come from the Israel Democracy Institute’s annual Democracy Index. I would guess that the generals are not exactly quaking in their boots. But given the damning criticism of the army included in the Winograd Report (available in Hebrew here) on the Second Lebanon War, issued earlier this year, it’s rather surprising that the IDF remains so popular. Or is it?

In fact, the army remains far more popular than every other public institution in the country. Only 35 percent trust the Supreme Court (a drop of 12 points), only 17 percent the prime minister, only 37 percent the media.

Does this mean that Israel is a modern Prussia, taking glory in the macho military values embodied in its armed forces? Not exactly. Israelis are hardly alone in admiring their fighting men. In fact, armies tend to be wildly popular institutions in most countries. I recall an essay by Jorge Luis Borges (I can’t find the specific reference right now) in which he explained the central place of the army in the society of Argentina and the admiration in which it was held-despite that army’s penchant for staging coups d’etat and pushing those who don’t admire it out of airplanes.

Misunderstanding Identity: The Left and the Neocons Unite

America is the land of freedom. It is the world’s standard for democracy; its ideals of personal freedom and civil rights are the envy of all enlightened citizens of the world.

If you grew up in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, as I did, this is what you learned at school.

The myth of American freedom is a strong one, and one reason it’s strong is that it contains a lot of truth. But the democracy of the United States is hardly perfect and it does not necessarily produce enlightened governments, leaders, and policies.

Paradoxically, the myth of American freedom is strongest today in two groups that see themselves as negations of the other—the neoconservatives and that slice of the American left that might be best defined as subscribers to Harpers and The New York Review of Books. The neocons believe that the way to make the world a better place is for America to export its democracy forcefully—and with force, if necessary. The leftists wouldn’t force anything on anyone, but they do think that if other peoples would just be reasonable and adopt the U.S. constitution, war, conflict, and unreason would give way to well-mannered societies much like those in America’s great suburbs.

There’s a textbook example of this on display in the current issue of Commentary, where that magazine’s assistant editor, David Billet, reviews Bernard Avishai’s new book, The Hebrew Republic: How Secular Democracy and Global Enterprise will Bring Israel Peace at Last.