Haim Watzman

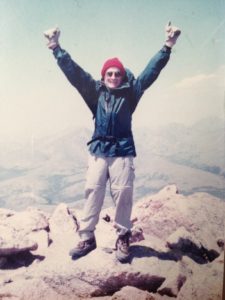

This dvar Torah, translated from this week’s issue of Shabbat Shalom , the weekly Shabbat pamphlet of the religious peace group Oz Veshalom is dedicated to the memory of my father and teacher Sanford “Whitey” Watzman, who left us six years ago on 2 Av.

אפשר לקרוא בעברית כאן: “איכה הייתה הזונה לאהובה”

“Alas, she become a harlot, the faithful city” laments the prophet Isaiah (1:21) in the haftarah for Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat preceding Tisha B’Av. Isaiah is not the only prophet to portray the city of Jerusalem, and the people of Israel, as a harlot—it is a motif that other prophets also use. The most notable of these is Hosea, in whose book it constitutes the underlying metaphor. On the face of it, the comparison seems simple. There are women who are unfaithful to their husbands and who lie with other men, either to satisfy their sexual passions or to earn money. When the people of Israel worship other gods and act in violation of the values of the Torah, they are like harlots.

“Alas, she become a harlot, the faithful city” laments the prophet Isaiah (1:21) in the haftarah for Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat preceding Tisha B’Av. Isaiah is not the only prophet to portray the city of Jerusalem, and the people of Israel, as a harlot—it is a motif that other prophets also use. The most notable of these is Hosea, in whose book it constitutes the underlying metaphor. On the face of it, the comparison seems simple. There are women who are unfaithful to their husbands and who lie with other men, either to satisfy their sexual passions or to earn money. When the people of Israel worship other gods and act in violation of the values of the Torah, they are like harlots.

But the word “harlot” (zonah in Hebrew) in its various forms is not just a metaphor in the Tanach.