Haim Watzman

On to the down-home bargain hotel in shabby-to-slummy Tiberias, where we will spend the long second weekend of Pesach. From our window we have a view, not of Lake Kinneret, but of the rubbish-filled yards of abandoned buildings up the street, and the lonely olive trees that dot the mountain slopes between the upper city’s housing-project neighborhoods.

The next morning, Thursday, the eve of the holiday, we continue north, as far north as we can go, to Metula. We take a right at the gate, then turn right again and again to reach the entrance to the Ayun Reserve. A stream of that name wells up a bit further north, in Marjayoun—I saw it three and a half decades ago, when I shuttled through the town time and again as a soldier serving unenthusiastically in Lebanon. When it crosses the Israeli border, it enters a narrow canyon and spills down a steep series of waterfalls, into the Hula Valley. Thirteen years ago the stream dried up, when Hezbollah diverted the source springs in the Lebanese town to irrigate the fields nearby. A few years ago, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority brought the stream back to life by piping in water from the Dan, a mightier stream to the southeast. Dan and Ayun, along with Hatzbani and Banyas, are the four headwaters of the Jordan, fed by melted snow from Mt. Hermon filtered through limestone strata laid down by primordial seas and pushed up by ancient cataclysms.

Seven years ago, on this holiday, our son died. Niot, our third headwater, was like a stream. He bubbled up, burbled, flowed over rapids, made all around him green and alive. Year round, year by year, for twenty years.

Yom HaZikaron

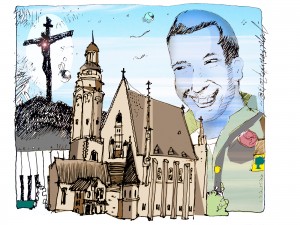

Desertion — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

illustration by Avi Katz

The picture I see each morning when I turn on my computer is of my younger son, Niot, in a graveyard. His hands are on his hips, his head is cocked, his eyes look straight at me, and his lips are pressed into a half-smile that says, “What, you again?” He’s wearing a gray coat, striped on the shoulders with the straps of a red backpack. Under the coat is a blue Adidas sweatshirt and on his head is an indescribable hat, which perhaps has something to do with a defunct Polish yeshiva. The cemetery is in Poland, and the photograph was taken during his high school class trip to the concentration camps. Now he’s in another cemetery.

I didn’t miss him then. It was a time when I never missed any of my children. That is, I missed them in the sense that I enjoyed when they were home and wondered how they were doing when they were not, but I never felt that they were out of reach, that I desperately needed to talk to or touch them; I never feared that they would not come back. No longer, because Niot went away and didn’t.

When a child dies, he becomes incessantly present. Niot is always in my thoughts, all the time, and not in the back as he was when he was off at school or in the army. He’s always looking at me and asking, “What, you again?”

He’s close up in my mind, and right there on my computer screen, but so distant. As of the Shabbat in the middle of Pesach it’s three years now, and he grips my heart but recedes; I hold him tight but he is ever more distant.

Niot connected with friends and basketballs, not with poetry, but I often think of poetry when I think of him. Right now it’s a poem by one of my favorite living American poets, Sharon Dolin, and it’s called “The Problem of Desertion.” That’s the title, but it’s also the first line, because after it the poem goes like this:

occurs when time feels like space

and the dead are stuck

on shore

As if time were something you have to push your way through. But am I not the one on shore, the one who stayed behind when Niot went off to Poland, when he went off to Golani, when he went off to Eilat and down into the Red Sea and never came back?

A Him to him — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

My Dear Herr Kapellmeister,

It’s spring here in Jerusalem. Fields, yards, and the few vacant lots that remain in this increasingly overbuilt city are burgeoning with blood-red anemones. Two weeks ago, Ilana and I visited a hill not too far away that is carpeted with purple lupines, growing over the ruins of an ancient city. The flowers perfume the air and after each of the rainy season’s final drizzles the soil itself smells alive.

illustration by Pepe Fainberg

Perhaps spring came late in Leipzig in 1727. How else to explain the sorrow of that opening chord in the organ and strings, the melody that rises, then falls as if it can go on no longer, only to rise again? Why, if your Redeemer died for your sins, did you sigh rather than celebrate? Why, if the equinox had passed and the day was already longer than the night, did you have the choir, entering just as the instrumental melody comes to rest, stun me with a wail of helplessness, of hopelessness, “Come ye daughters, share my lament—see him!”

Yes, I know, “Him,” with a capital H. A big Him for you, a little him for me.