Haim Watzman

“It is a heavenly chicken,” he pronounced. “There is no pleasure on this earth greater than inhaling the scent of a cooking chicken.”

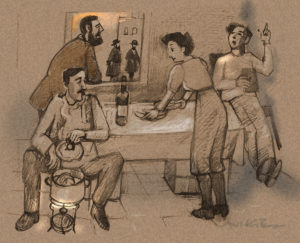

“How about an orgasm?” suggested Yanai, tipped back against a corner with his legs stretched out, dressed in a white shirt and paint-splattered work pants. The corner went dim as the final ray of the setting sun abandoned the window of Devorah Hannah’s room in Jerusalem’s Fruits of Labor neighborhood. Behind the aroma of the cooking chicken was a dank scent of mildew, brought on an hour before by a cloudburst that had come two weeks too early on that Yom Kippur eve of 1911.

“All great orgasms are, ultimately, alike,” Zealot considered, preening his moustache, “but each excellent repast is excellent in its own way.”

“Zealot has never had either,” Devorah Hannah informed Eliezer, as she set her table for four. The table was the board that served as her bed, with an additional crate added to each leg, with a white cotton sheet serving as a tablecloth. A bottle of Rishon Letzion was already open and waiting. Eliezer gazed out the window at men in black frock coats and black hats striding toward synagogues. He wore the brown gabardine suit that he generally put on only for his meetings with Ottoman officials or Baron Rothschild’s men.

“I can’t read any more,” Yanai sighed, putting down his copy of Brenner’s new novel, On This Side and That.

“Too dark?” Eliezer asked.

“The darkness of the soul,” Yanai said, slowly rising, then pushing the rickety chair toward the table. He stretched his lanky frame and yawned. “When do we eat?”