Haim Watzman

This is an English version of the dvar Torah that appears in issue 1208 of “Shabbat Shalom,” the weekly portion sheet published by the religious peace movement Oz Veshalom. It is dedicated to the memory of my father and teacher Sanford “Whitey” Watzman, who left us seven years ago on 2 Av.

Many years ago, when I worked as a journalist, I attended a press conference at a conservative research institute in Jerusalem. I don’t recall exactly what the subject was, but I do remember that the institute’s director, who had served in an elite unit in the US Army, claimed that he could prove scientifically that the State of Israel had been in the right in a recent military action that had been loudly criticized by the rest of the world. After I and several other reporters settled ourselves in the small meeting room, he rose to speak. “I’ll start with the creation of the world,” he began. Realizing that the press conference would be very long and grueling. I mumbled an excuse of some sort, got up, and left.

Many years ago, when I worked as a journalist, I attended a press conference at a conservative research institute in Jerusalem. I don’t recall exactly what the subject was, but I do remember that the institute’s director, who had served in an elite unit in the US Army, claimed that he could prove scientifically that the State of Israel had been in the right in a recent military action that had been loudly criticized by the rest of the world. After I and several other reporters settled ourselves in the small meeting room, he rose to speak. “I’ll start with the creation of the world,” he began. Realizing that the press conference would be very long and grueling. I mumbled an excuse of some sort, got up, and left.

The choice of the right starting point is part of the art of storytelling. Tracing the sequence of causes that led to any given event will always lead to the creation of the world, given that, at least according to the modern scientific view, every event is the consequence of a previous event, going back to the dawn of time. But it’s not only that beginning every story at the creation is tiring. It’s simply wrong, both literarily and in principle. Because the place where the story begins needs to foreshadow the end that the storyteller wants to arrive at.

dvar Torah

How Has the Harlot Become the Beloved / Dvar Torah, Parshat Devarim

Haim Watzman

This dvar Torah, translated from this week’s issue of Shabbat Shalom , the weekly Shabbat pamphlet of the religious peace group Oz Veshalom is dedicated to the memory of my father and teacher Sanford “Whitey” Watzman, who left us six years ago on 2 Av.

אפשר לקרוא בעברית כאן: “איכה הייתה הזונה לאהובה”

“Alas, she become a harlot, the faithful city” laments the prophet Isaiah (1:21) in the haftarah for Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat preceding Tisha B’Av. Isaiah is not the only prophet to portray the city of Jerusalem, and the people of Israel, as a harlot—it is a motif that other prophets also use. The most notable of these is Hosea, in whose book it constitutes the underlying metaphor. On the face of it, the comparison seems simple. There are women who are unfaithful to their husbands and who lie with other men, either to satisfy their sexual passions or to earn money. When the people of Israel worship other gods and act in violation of the values of the Torah, they are like harlots.

“Alas, she become a harlot, the faithful city” laments the prophet Isaiah (1:21) in the haftarah for Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat preceding Tisha B’Av. Isaiah is not the only prophet to portray the city of Jerusalem, and the people of Israel, as a harlot—it is a motif that other prophets also use. The most notable of these is Hosea, in whose book it constitutes the underlying metaphor. On the face of it, the comparison seems simple. There are women who are unfaithful to their husbands and who lie with other men, either to satisfy their sexual passions or to earn money. When the people of Israel worship other gods and act in violation of the values of the Torah, they are like harlots.

But the word “harlot” (zonah in Hebrew) in its various forms is not just a metaphor in the Tanach.

When I Left Egypt—When I Left Jerusalem / Dvar Torah, Parshat Devarim

This dvar Torah, translated from this week’s issue of Shabbat Shalom , the weekly Shabbat pamphlet of the religious peace group Oz Veshalom is dedicated to the memory of my father and teacher Sanford “Whitey” Watzman, who left us four years ago on 2 Av.

This dvar Torah, translated from this week’s issue of Shabbat Shalom , the weekly Shabbat pamphlet of the religious peace group Oz Veshalom is dedicated to the memory of my father and teacher Sanford “Whitey” Watzman, who left us four years ago on 2 Av.

Can there be two more contradictory statements describing God attending to the voice of his people than the one at the Burning Bush and the one at the Plains of Moab? At the first, God tells Moses: “I have marked well the plight of my people in Egypt and have heeded their outcry because of their taskmasters; yes, I am mindful of their sufferings” (Exodus 3:7). In contrast, in this week’s portion, Devarim, when Moses recounts the story of the spies and the Ma’apilim (those who sought to disregard God’s decree that the members generation that left Egypt would not enter the Land of Israel), he declares: “Again you wept before the Lord; but the Lord would not heed your cry or give ear to you” (Deuteronomy 1:45). The first statement prepares Moses for the Exodus from Egypt. The second prepares the Children of Israel for the ultimate destruction of their commonwealth and the Exile.

But the contradiction actually goes well beyond that. On a simple reading of Exodus, the redemption from Egypt seems not to be the result of any good deeds or merits of the Children of Israel. When we left Egypt, we left because the term of the Exile, pronounced to Abraham at the time of the Covenant between the Parts (Genesis 15), had come to an end. Presumably the Israelites were crying out to God throughout their enslavement, and did not begin doing so only when Moses reached the Burning Bush. The same pattern appears later, at the time of the Return to Zion (Shivat Tzion) from the Babylonian Exile. This second redemption begins after the seventy-year term prophesized by Jeremiah comes to an end, not because the Exiled Jews have been righteous: “In the first year of King Cyrus of Persia, when the word of the Lord spoken by Jeremiah was fulfilled, the Lord roused the spirit of King Cyrus of Persia to issue a proclamation throughout his realm” (Ezra 1:1).

But things were quite different when we left Jerusalem, at the time of the destruction of both the First and Second Temples. The Jews go into exile not because the prearranged date for it has arrived, not because a term of years was set in advance for their sojourn in the Land of Israel. The Torah and prophets stress that the Land vomited the people out because of their evil actions.

Not a Third Time — Dvar Torah in Memory of My Dad

The dawn of sovereignty and the end of sovereignty, divine providence and divine concealment, standing on the verge of the Land of Israel and gong into exile—the first chapters of the book of Deuteronomy, which we read this week in the annual cycle of Torah readings, seem to mirror and contrast the themes of the fast of the Ninth of Av, which always falls in the week after it is read. The cycle is deliberately arranged so that we always begin our reading of Deuteronomy on Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat before Tisha B’Av, the fast that mourns the destruction of the First and Second Temples and the beginnings of the Babylonian and Roman exiles. The most commonly cited connection between the fast and the Torah reading is that the word “eichah,” the exclamation that means “how can this be endured!” (The word also appears in the week’s haftarah from Isaiah and is a refrain in the Scroll of Lamentations read on Tisha B’Av.) But there is much more. The clear message conveyed by the days between Shabbat Hazon and Tisha B’Av is that the Jewish nation was given a chance to establish an independent and moral society, one acting in the name of heaven and not for its own aggrandizement—and that we failed the test badly.

My father worked for many years as a journalist out of a sense of mission and a firm belief that a free press is one of the cornerstones of democratic society. And he believed that democracy was the best (if far from perfect) way of establishing and maintaining a moral human society. Democracy requires citizens to take responsibility for themselves. On the face of it, that seems to be the opposite of what the Torah demands.

The Missing Center — Thoughts on the Seder in Memory of My Son Niot

Haim Watzman

Haim Watzman

My annual meditation on Pesach and the Seder, in memory of my son Niot on the fifth anniversary of his death, written for Shabbat Shalom, the weekly Torah sheet published by the religious peace group Oz VeShalom–Netivot Shalom.

לגרסת המקור בעברית

A void yawns at the heart of the Haggadah, at the very center of the Seder. All we speak of on this long night leads to the central ritual precept—the eating of the Pesach sacrifice. We tell the story of the Exodus, sing “Dayenu” and, in obedience to Rabban Gamiliel, cite the three items that, if unmentioned, prevent us from having fulfilled the obligations of the Seder. Then we move from speech into action—we eat matzah, we eat maror. But there is no Pesach sacrifice to for them to be eaten with.

At the time of the twentieth-century return to Zion, there were calls to resume the Pesach sacrifice. A halakhic polemic ensued. Rabbis and scholars traded fine distinctions regarding the laws of sacrifices, of the Temple, of the priests, but very few of them spoke explicitly about what it would mean to turn the great nullity of the Seder night into a manifest presence.

Sefer HaAggadah offers a surprising midrash about Pharaoh on the night of the smiting of the first-born. The source is Midrash Tanhuma, but Bialik’s and Ravnitzky’s version offers a more potent vision: “Pharaoh went among his servants, from door to door, placing each one in his retinue, and walked with them that night down every street and called out ‘Where is Moses? Where does he live?’”

I want to focus on that picture, not on the story as a whole. The picture has two elements: first, just prior to the Exodus from Egypt—that is, on the first Seder night—Pharaoh leaves his home. He goes from door to door like a beggar seeking bread and the warmth of a home and a family.

Non Sequitur — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

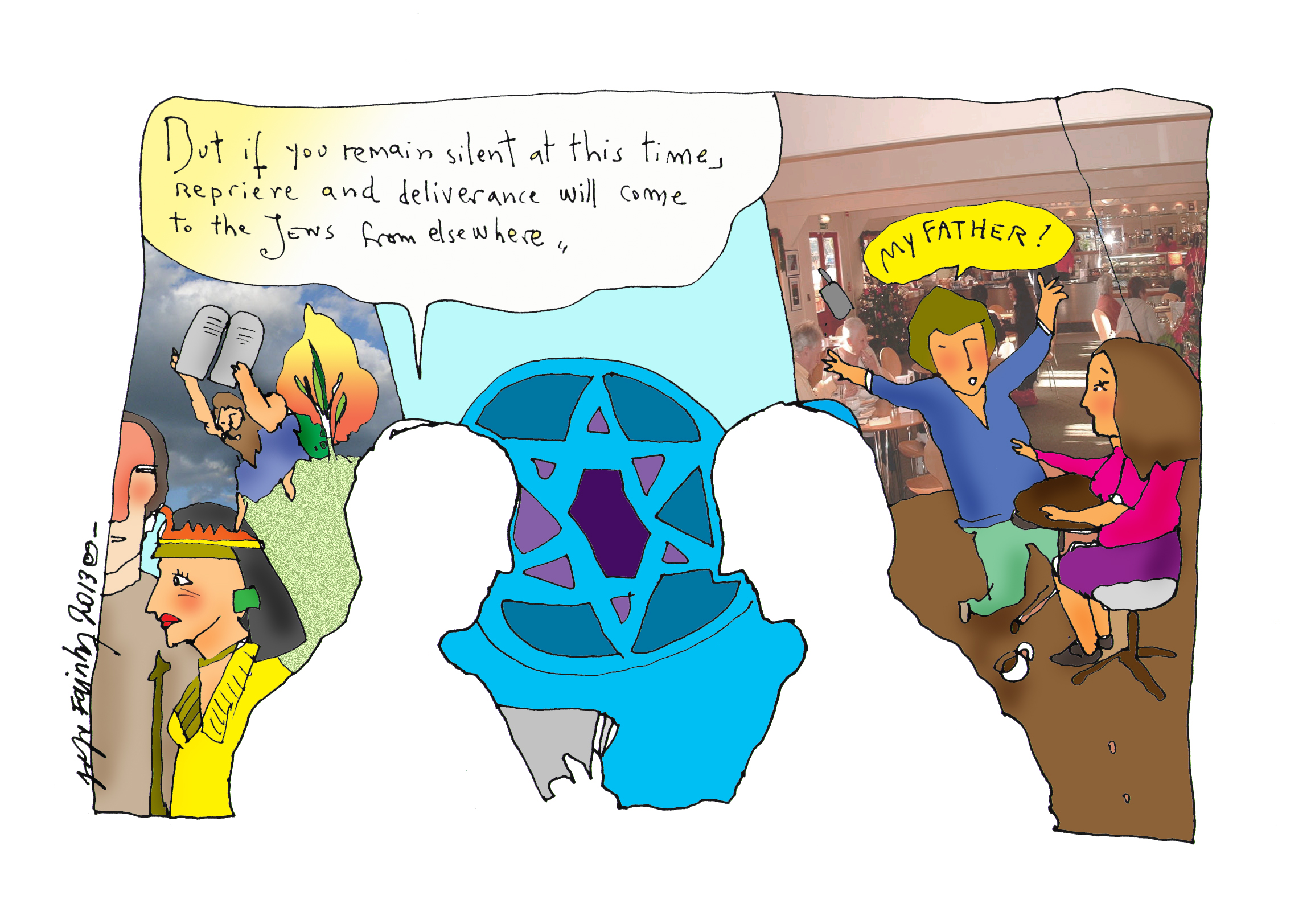

God knows how Eliezer’s mind works. It goes off into other dimensions every time I try to have a serious conversation with him. That’s what happened on Purim this year. I waited through the entire reading of the megillah, the Book of Esther, to point out to him Chapter 4, verse 14, which I’d never really thought about before.

illustration by Pepe Fainberg

“Ki ‘im taharishi ba-‘et ha-zot’ revah ve-hatzalah ya‘amod le-yehudim mi-makom aher,” Eliezer reads as my finger traces the word. He translates: “‘But if you remain silent at this time, reprieve and deliverance will come to the Jews from elsewhere.’ So?”

“So this is what Mordecai says to Esther when he tells her about Haman’s plot to kill the Jews,” I point out. “That she really doesn’t have to do anything, because the Jews are going to be saved anyway.”

“Well, if that’s God’s plan,” says Eliezer, “then I guess he’s right. What’s the big deal?”