Haim Watzman

The field school guide leads us along a path that skirts ripening stalks and ascends a low hill. The air is still, heated from above by a sun unseen through a dusty haze. At the top I count my family. Ilana is right behind me; my youngest, Misgav, stands next to the guide, looking out on the plain. I hold out my hand to take Niot’s, closing my fingers around a void. He is gone. I turn and see him running, running through the wheat.

Niot had a habit of running off, not in exuberance, like a dog released from a leash, but in fear. Once, when our dentist took out the set of pointy and shiny tools with which he used to probe mouths, Niot leapt from the chair, whizzed out of the clinic and the building. It took twenty minutes for me, the dentist, the hygienist, and his older brother to ambush him and bring him back. His teeth were not examined.

This time, however, there is no reason for fear. We are having a good time and he is getting along with the other kids. Just a few minutes before he had been singing at the top of his lungs. When I call out to him, he does not turn. I lope down the hill, at a canter, so as not to incite him to go any faster. But as I descend, the wheat stalks, taller than he, hide him. Now it is I who am frightened. Who knows what he will do—find his way to the road on the other side of the field, fall into a pit, encounter a scorpion or dangerous stranger.

In the years since Niot left us forever, I also pursue him, but not so fast as to incite him to run faster. I live in fear that I will lose sight of him, that he will disappear beyond my mind’s horizon. How can that be? Five years after his death, I think of him constantly. But the wheat conceals him.

loss

Non Sequitur — “Necessary Stories” from The Jerusalem Report

Haim Watzman

God knows how Eliezer’s mind works. It goes off into other dimensions every time I try to have a serious conversation with him. That’s what happened on Purim this year. I waited through the entire reading of the megillah, the Book of Esther, to point out to him Chapter 4, verse 14, which I’d never really thought about before.

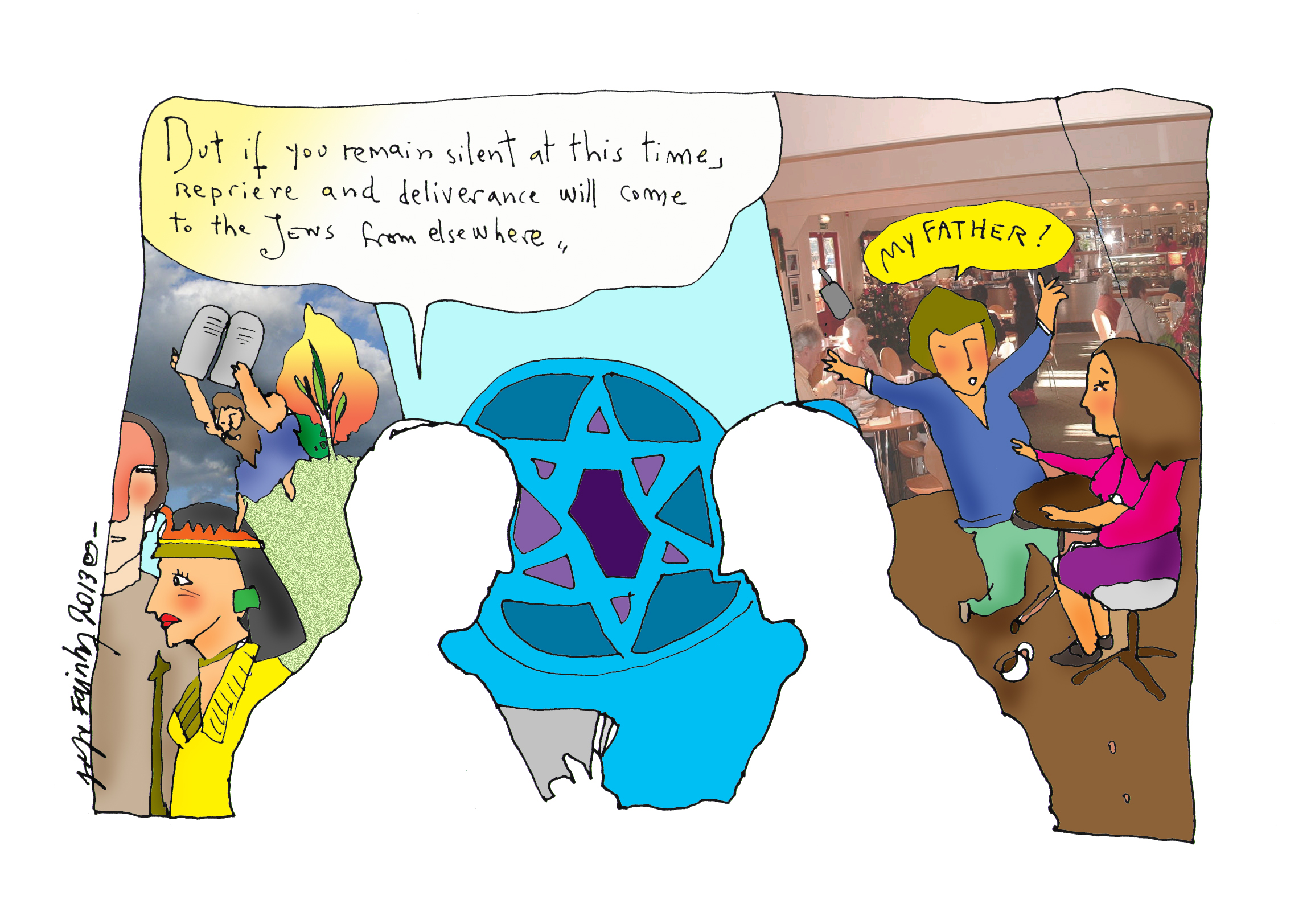

illustration by Pepe Fainberg

“Ki ‘im taharishi ba-‘et ha-zot’ revah ve-hatzalah ya‘amod le-yehudim mi-makom aher,” Eliezer reads as my finger traces the word. He translates: “‘But if you remain silent at this time, reprieve and deliverance will come to the Jews from elsewhere.’ So?”

“So this is what Mordecai says to Esther when he tells her about Haman’s plot to kill the Jews,” I point out. “That she really doesn’t have to do anything, because the Jews are going to be saved anyway.”

“Well, if that’s God’s plan,” says Eliezer, “then I guess he’s right. What’s the big deal?”