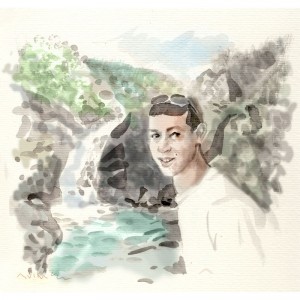

In memory of my younger son, Niot, eight years after his death at the age of 20, during Pesach. From the Pesach 2019 issue of Shabbat Shalom, the weekly Torah sheet of the religious peace movement, Oz Veshalom.

In memory of my younger son, Niot, eight years after his death at the age of 20, during Pesach. From the Pesach 2019 issue of Shabbat Shalom, the weekly Torah sheet of the religious peace movement, Oz Veshalom.

להורדת הגליון של “שבת שלום בעברית”

“The slaves of time are slaves of a slave, only the servant of the Lord is free,” sang Rabbi Yehuda Halevi (in Peter Cole’s translation). The poet is referring to the view that, when they left Egypt, the Children of Israel went not from slavery to freedom but rather from slavery to slavery. In Egypt we were slaves to Pharaoh, and when we left Egypt we became slaves to God. In Egypt we lived under the yoke of Pharaoh, king of Egypt, and since then we have lived under the yoke of the commandments given to us by the King of all Kings.

But this account of the Exodus is problematic. The biggest problem is that it contradicts the status of slaves as defined by the Torah and Jewish law. A Hebrew slave is obligated to observe fewer precepts than a free person (a free male, not a female; the gendered nature of Torah obligations is an important issue but not germane to the matter at hand). Furthermore, the view that we remain slaves following the Exodus is a problematic one today, given our revulsion from slavery and our belief that it exemplifies radical injustice. I doubt that any reader of this essay can easily imagine life as a chattel who is unable to come and go as he wishes and who is entirely dependent on the mercies of his master.

In other words, religious Jews who are also modern Westerners and citizens of democratic countries can only feel unease with this depiction of the Exodus. The idea that we are slaves—even if God’s slaves—is simply incompatible with the lives of people who live in law-based states that are ruled not by kings but by elected officials subject to laws and the oversight of the other branches of government, the people, and the media. Our acceptance of authority today presumes our right to criticize, to express doubt, to challenge, and to be active partners in the creation of the norms to which we are subject.

Yet, even today, the concept that we were once slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt and today are slaves to God is very much part of how we think of Pesach and the Seder. I suggest, however, that it is not the approach of the Jewish sages. I learn this from an examination of how the word “slave” is used in the Haggadah.

The word “slave” (‘eved / עֶבֶד) appears about thirty times in the text of the Haggadah, but it does not bear the same meaning everywhere it appears. In fact, it is used in four different ways: